Summary

In IATP’s 2021 report Closed out: How U.S. farmers are denied access to conservation programs, we showed that for years, farmers have been turned away from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) two flagship conservation payment programs, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). Between 2010 and 2020, only 42% of CSP applicants and 31% of EQIP applicants were awarded contracts.1

This new report examines how EQIP in particular pays for agricultural practices that are not environmentally beneficial or in some cases actively make the environment worse. Specifically, this report examines the implementation of the program in the 12 states most frequently classified as “The Midwest:” Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota.

We look at 2020 USDA data by state, analyzing number of contracts awarded, dollar amounts awarded and which practices are most popular. We also incorporate data gathered by others examining whether or not EQIP serves farmers of color well.

This report finds that current resources are being misdirected to large, polluting operations while thousands of farmers are being turned away from contracts that could help them pay for conservation improvements and help their bottom lines. Reforms are needed to ensure that EQIP funds only go toward truly environmentally beneficial practices. USDA can better allocate finite resources to those who need it most, including those who integrate more climate friendly, agroecological practices and systems.

Introduction

Climate change continues to be a major disruptor of food and farm systems across the globe. The recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change underscored the urgent need for more resilient systems for farmers and eaters to withstand the shocks of an increasingly unpredictable climate.2 Unfortunately, the current agricultural marketplace does not reward farmers for resilience. Instead, it pressures farmers to buy into a system of high-cost, industrial farming methods that leave the water and air worse off while keeping many farmers strapped for cash year to year.

This is where EQIP comes in. As Closed Out detailed, since EQIP’s inception in the 1996 Farm Bill, it has helped farmers pay for farming methods that can increase both economic and environmental resilience in the face of climate change — helping reimburse farmers for practices focused on increased soil health, cover crops, pasture management, buffers between waterways and tilled farmland, and many other tried-and-true methods of reducing risk in farming. At the same time that EQIP pays farmers to improve their land and mitigate climate risks, it is also subsidizing many highly polluting farms that are actively making the climate crisis worse.

What’s in an EQIP Factory Farm Practice?

As IATP’s research in Emissions Impossible explained, over 90% of the emissions from corporate meat and dairy companies come from the livestock supply chain.3 These are the emissions that come from raising livestock and growing livestock feed. Some of the most intensive emitting nodes of the livestock supply chain are large concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), facilities that are commonly referred to as “factory farms.” These CAFOs keep livestock and poultry in confined quarters with little to no access to pasture or even the outdoors and require industrial solutions to issues like manure management.

Some of these industrial solutions, like manure lagoons, are disasters waiting to happen. Not only do they emit high amounts of methane and nitrous oxide,4 but they are also highly vulnerable to natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods, which can put neighbors and local water at risk.5 CAFOs decouple grazing animals from grasslands, which can be an efficient and ecological alternative to intensive feedlot operations. The less farmers rely on natural manure spreading via pastured livestock means farmers apply more synthetic fertilizers, which emit even more nitrous oxide.6 For years, the Environmental Working Group tracked EQIP payments, practices and effects on environmental factors like water quality.7 Through this report, we hope to build on the work that has already been done by others and show the combined climate and economic risks of misallocated EQIP funds.

Of the over 300 practices that EQIP supports through cost-share payments, we have identified 10 that we label as “industrial” or “factory-farm friendly.” These practices include using include waste storage facilities that prop up CAFOs and building underground outlets that aid in the conversion of natural systems such as wetlands into intensive crop production. In a sense, while these practices might improve environmental outcomes, they are cleaning up the messes created by industrial farming using federal money that would be better used on truly agroecological practices.

At a large enough scale, any practice can help prop up big factory farms, but there are a handful of EQIP practices that we consider the worst offenders. After reviewing all EQIP practices that were funded in 2020 in Midwest states, we narrowed the list to practices that perpetuate unnatural systems. This included practices that disrupt the natural flow of water and many practices that incentivize farmers to keep livestock in CAFOs and away from pastures. The list we compiled is by no means comprehensive. For the purposes of this paper, the 10 industrial practices are listed below.

Ten of the worst industrial practices included in EQIP

Essentially, underground outlets are the pipes and tubes that transport surface water from fields to creeks, streams or other bodies of water. This practice drains wetlands and increases the volume of water in streams and rivers, leading to more erosion and the carrying of excess nutrients to places like the Gulf of Mexico. The practice is often used in fields that have persistent standing water issues.

Often paired with underground outlets, this practice is how surface water in fields is carried away to nearby ditches and streams. These are commonly referred to as drainage tiles.

Waste storage facilities are structures built to contain large amounts of livestock manure. To keep the manure contained, these facilities often have large embankments and are intended to prevent seepage into soil and groundwater.

This practice puts a hard surface over storage facilities for animal manure. The intent is to prevent flooding or other ways of waste escape.

Once a waste storage facility is no longer needed, this practice helps pay for the decommissioning of the facility, which can include the pumping out of any and all liquid manure, removing concrete/embankments or even converting it to a freshwater pond.

This practice helps pay for pipes or other “conduits” to transfer liquefied animal manure to a waste storage facility.

On farms where livestock die with frequency, this practice helps pay for disposal facilities to keep the livestock carcasses from contaminating soil or water. The facility can be in the form of a concrete bunker or other bermed structure.

In case of “catastrophic events” like the 2020 Iowa derecho, hurricanes or other sudden events that cause mass livestock death, this practice helps pay for the disposal of animal carcasses. While farms of all sizes can take advantage of this practice, it still largely benefits large factory farms.

This practice helps pay for gutters and other diversions of water runoff from roofs to ensure the water does not arrive in high volumes in contaminated areas. The practice decreases opportunities for water contaminated with pathogens, fertilizers, pesticides, medications or excess nutrients to enter surface waterways and groundwater. While farmers of all sizes and models might use this practice, and fewer federal funds went to it in 2020 than other practices on this list, it still is a practice directed toward operations with large buildings and associated confinements and feedlots.

This practice pays for the construction of a pumping plant that can have many uses, including the transport of liquid manure, the draining of surface water or the creation of drinking water reservoirs for livestock. We include this practice in the list of industrial practices because of its use for liquid manure transfer, an issue that mostly large-scale factory farms face.

The above EQIP practice descriptions are summarized from the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS’s) Conservation Practices page.8

Source: National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition,9 Natural Resources Conservation Service10

How much EQIP money goes to industrial practices?

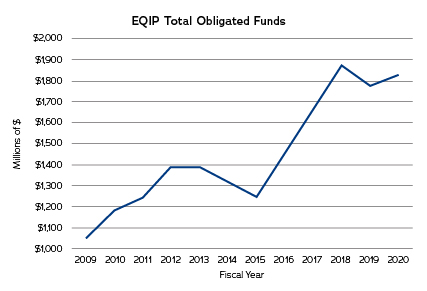

Before the 2002 Farm Bill, CAFOs were specifically excluded from EQIP funding.11 EQIP was started with the express intent of helping farmers put in place sound conservation on their land, but since the inclusion of CAFO funding in EQIP, more and more resources have gone toward industrial practices. Below is a chart from the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition showing the growth in total obligated funds to EQIP since 2009.

By law, 50% of EQIP funds are earmarked for livestock-specific practices. While some of that money does go toward practices like rotational grazing and water conservation-related practices, an inordinate amount goes toward industrial practices.

Conservationists and state technical advisory committees (STACs) in each state are empowered to decide which kinds of practices to prioritize in their state. While some states may focus solely on program implementation, others might approach their work with a grazing focus, forestry, row crops, or other mode of agriculture. States with large amounts of grazing might focus more on practices that improve rangeland and pastureland health, whereas states with large amounts of CAFOs might focus on practices friendlier to such operations. If a state does not meet the 50% livestock set-aside, that funding can be redirected to other states that can.

Here’s how much each Midwest state spent on the 10 practices we categorize as “industrial” in 2020.

2020 Spending on Practice

|

Practice

|

Illinois

|

Indiana

|

Iowa

|

Kansas

|

Michigan

|

Minnesota

|

|

Underground Outlet

|

$2,477,227

|

$651,421

|

$1,731,446

|

$866,096

|

$67,430

|

$783,546

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,410,063

|

$1,804,398

|

$2,097,488

|

$380,200

|

$0

|

$3,024,553

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$1,094,481

|

$1,586,552

|

$2,659,876

|

$994,789

|

$3,472,423

|

$3,472,423

|

|

Subsurface Drain

|

$280,099

|

$280,924

|

$195,118

|

$15,437

|

$16,287

|

$281,771

|

|

Closure of Waste Impoundment

|

$223,391

|

$110,482

|

$11,595

|

$570,307

|

$0

|

$96,231

|

|

Manure Transfer

|

$188,860

|

$211,738

|

$52,781

|

$291,058

|

$282,574

|

$222,867

|

|

Animal Mortality Facility

|

$161,576

|

$457,792

|

$0

|

$0

|

$151,894

|

$270,574

|

|

Emergency Animal Mortality Management

|

$146,673

|

$1,199

|

$89,718

|

$4,248

|

$0

|

$196,324

|

|

Roof Runoff Management

|

$79,401

|

$125,281

|

$38,091

|

$0

|

$58,138

|

$24,436

|

|

Pumping Plant for Water Control

|

$30,642

|

$20,728

|

$52,629

|

$419,903

|

$31,771

|

$111,682

|

|

2020 total spent on EQIP industrial practices

|

$6,092,413

|

$5,250,515

|

$6,928,742

|

$3,542,038

|

$4,080,517

|

$8,484,407

|

|

2020 total spent on EQIP

|

$16,346,974

|

$25,476,807

|

$28,784,753

|

$34,920,524

|

$16,685,176

|

$27,543,385

|

|

2020 Percentage of total EQIP funds spent on industrial practices

|

37.3%

|

20.6%

|

24.1%

|

10.1%

|

24.5%

|

30.8%

|

2020 Spending on Practice

|

Practice

|

Missouri

|

Nebraska

|

North Dakota

|

Ohio

|

South Dakota

|

Wisconsin

|

|

Underground Outlet

|

$1,487,710

|

$878,405

|

$0

|

$71,946

|

$56,689

|

$224,977

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,760,845

|

$151,480

|

$0

|

$2,603,966

|

$514,480

|

$1,342,055

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$612,041

|

$297,120

|

$66,605

|

$2,027,557

|

$1,049,885

|

$2,100,627

|

|

Subsurface Drain

|

$17,168

|

$0

|

$0

|

$93,010

|

$0

|

$268,596

|

|

Closure of Waste Impoundment

|

$685,773

|

$58,503

|

$0

|

$0

|

$116,039

|

$1,060,969

|

|

Manure Transfer

|

$796,500

|

$27,034

|

$12,416

|

$19,200

|

$2,840

|

$428,190

|

|

Animal Mortality Facility

|

$40,671

|

$0

|

$0

|

$45,154

|

$139,055

|

$225,082

|

|

Emergency Animal Mortality Management

|

$506

|

$12,341

|

$0

|

$0

|

$89,994

|

$0

|

|

Roof Runoff Management

|

$0

|

$24,436

|

$0

|

$160,741

|

$6,994

|

$27,004

|

|

Pumping Plant for Water Control

|

$202,943

|

$954,728

|

$376,221

|

$68,406

|

$289,102

|

$187,106

|

|

2020 total spent on EQIP industrial practices

|

$5,604,157

|

$2,404,047

|

$455,242

|

$5,089,980

|

$2,265,078

|

$5,864,606

|

|

2020 total spent on EQIP

|

$32,395,648

|

$24,765,542

|

$21,204,203

|

$22,664,568

|

$17,545,320

|

$32,943,555

|

|

2020 Percentage of total EQIP funds spent on industrial practices

|

17.3%

|

9.7%

|

2.1%

|

22.5%

|

12.9%

|

17.8%

|

Source: Natural Resources Conservation Service12

Do any states have positive, agroecological models?

As the data above shows, some states commit many more resources to harmful practices than others. One state that stands out as a positive model is North Dakota, where less than $500,000 across the whole state is spent on industrial EQIP practices. North Dakota is a holdout state regarding factory farms: It continues to have strict protections for family farms and legal definitions of what is considered a farm.13

While states such as Kansas, Missouri and Wisconsin all have high EQIP expenditures, how that money is spent can differ widely from state to state. Kansas in particular spends a substantial amount of money on more agroecological practices, whereas Wisconsin spends quite a bit on industrial practices, with Missouri somewhere in between. Members of the public are encouraged to join their NRCS state technical advisory committees (STACs) to help shape implementation of Farm Bill conservation programs such as EQIP. In many cases, the differing state priorities can be traced to decisions made by STACs.

Below is a look at the top 5 EQIP practices by dollar amount in 2020, as well as the number of contracts awarded for that practice in the state. In general, the more contracts awarded, the more farmers served by the program.

Practices like waste facility cover and waste storage facility consistently rank in the top five practices while serving at most a few dozen farmers. In fact, while it may appear that the number of contracts would reflect the number of farmers served by a practice, farmers can hold multiple EQIP contracts at once. While there is little public data to show how common holding multiple contracts is, we refrain from equating number of contracts with number of farmers served.

Top Five EQIP Practices in the Midwest by State, 2020 (in $ spent)

Practice

|

$ Spent

|

Number of Contracts

|

Average Contract Size

|

Illinois

|

|

Underground Outlet

|

$2,477,227

|

391

|

$6,335.62

|

|

Water &

Sediment Control Basin

|

$2,016,172

|

410

|

$4,917.49

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,410,063

|

39

|

$36,155.46

|

|

Heavy Use Area Protection

|

$1,379,209

|

120

|

$11,493.41

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$1,094,481

|

10

|

$109,448.10

|

Indiana

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$5,441,614

|

995

|

$5,468.96

|

|

Nutrient Management

|

$3,172,547

|

336

|

$9,442.10

|

|

Brush Management

|

$2,060,971

|

388

|

$5,311.78

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,804,398

|

57

|

$31,656.11

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$1,586,552

|

39

|

$40,680,82

|

Iowa

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$6,328,447

|

1116

|

$5,670.65

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$2,659,876

|

42

|

$63,330.38

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$2,097,488

|

22

|

$95,340.36

|

|

Grade Stabilization Structure

|

$1,809,357

|

99

|

$18,276.33

|

|

Underground Outlet

|

$1,731,446

|

239

|

$7,244.54

|

Kansas

|

|

Terrace

|

$5,992,147

|

594

|

$10,087.79

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$3,570,475

|

597

|

$5,980.70

|

|

Conservation Crop Rotation

|

$2,049,493

|

138

|

$14,851.40

|

|

Prescribed Grazing

|

$2,039,888

|

848

|

$2,405.53

|

|

Obstruction Removal

|

$1,926,430

|

61

|

$31,580.82

|

Michigan

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$3,399,554

|

420

|

$8,094.18

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,808,356

|

40

|

$45,208.90

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$1,513,945

|

24

|

$63,081.04

|

|

Nutrient Management

|

$1,012,562

|

114

|

$8,882.12

|

|

Pest Management

|

$811,316

|

89

|

$9,115.91

|

Minnesota

|

|

Nutrient Management

|

$4,193,336

|

191

|

$21,954.64

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$3,472,423

|

43

|

$80,754.02

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$3,024,553

|

38

|

$79,593.50

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$2,479,935

|

343

|

$7,230.13

|

|

Pest Management

|

$2,076,385

|

117

|

$17,746.88

|

Missouri

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$5,296,458

|

1116

|

$4,745.93

|

|

Wildlife Habitat Planting

|

$3,899,944

|

442

|

$8,823.40

|

|

Fence

|

$2,573,371

|

524

|

$4,911.01

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,760,845

|

31

|

$56,801.45

|

|

Terrace

|

$1,672,075

|

151

|

$11,073.34

|

Nebraska

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$2,301,425

|

509

|

$4,521.46

|

|

Brush Management

|

$1,816,145

|

439

|

$4,137.00

|

|

Conservation Crop Rotation

|

$1,696,044

|

221

|

$7,674.41

|

|

Terrace

|

$1,637,850

|

170

|

$9,634.41

|

|

Fence

|

$1,553,610

|

329

|

$4,722.22

|

North Dakota

|

|

Nutrient Management

|

$3,844,719

|

180

|

$21,359.55

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$3,332,803

|

263

|

$12,672.25

|

|

Wildlife Wetland Habitat Management

|

$2,261,219

|

548

|

$4,126.31

|

|

Pipeline

|

$1,769,408

|

170

|

$10,408.28

|

|

Fence

|

$1,483,228

|

291

|

$5,097.00

|

Ohio

|

|

Nutrient Management

|

$3,541,257

|

305

|

$11,610.68

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$3,206,860

|

637

|

$5,034.32

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$2,603,860

|

95

|

$27,409.05

|

|

Brush Management

|

$2,079,532

|

1063

|

$1,956.29

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$2,027,557

|

69

|

$29,384.88

|

South Dakota

|

|

Pipeline

|

$3,350,597

|

386

|

$8,680.30

|

|

Fence

|

$2,385,851

|

436

|

$5,472.14

|

|

Trough or Tank

|

$1,049,885

|

498

|

$2,108.20

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$1,016,115

|

8

|

$127,014.38

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$1,000,827

|

219

|

$4,569.99

|

Wisconsin

|

|

Cover Crop

|

$6,195,557

|

766

|

$8,088.19

|

|

Forest Slash Treatment

|

$2,549,695

|

46

|

$55,428.15

|

|

Waste Storage Facility

|

$2,100,627

|

25

|

$84,025.08

|

|

Pond Sealing or Lining Concrete

|

$1,782,850

|

15

|

$118,856.67

|

|

Waste Facility Cover

|

$1,342,055

|

18

|

$74,558.61

|

|

Source: Natural Resources Conservation Service14

|

In the above table, the differences in impact between industrial practices and more environmentally beneficial practices could not be clearer. Non-industrial practices serve more contracts and likely interface with more farmers with need for financial assistance. While many farmers are served by these non-industrial practices, there are undoubtedly many more who would like to access EQIP funding but are unable to receive it due to lack of funds.

Meanwhile, many industrial practices such as waste storage facility cost upward of $100,000 per contract while serving relatively few farmers. The more money that goes toward these practices means that fewer people can access EQIP. As we outlined in Closed Out, over half of farmers nationwide who apply to EQIP are rejected from the program. We highlighted the need for more funding as a potential solution, but diverting money away from high dollar industrial contracts and into more environmentally beneficial ones can go a long way toward reaching more farmers.

Does EQIP Leave Out Farmers of Color?

According to data compiled by the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC), Midwest states awarded between 1-13% of their EQIP contracts to “socially disadvantaged producers,” the umbrella term used by USDA to describe farmers of color. In some cases, the low percentage of contracts awarded to farmers of color reflects a low total number of farmers of color in that state. However, there are states such as South Dakota where farmers of color are better represented in EQIP contracts, which in South Dakota’s case likely reflects the large number of farmers who identify as Native American in the state.

EQIP, similar to CSP, commits 5% of its funds to farmers of color. Despite this set-aside, only two Midwest states meet that 5% commitment — South Dakota and Michigan. Additionally, each state is free to do as much or as little outreach to fill the 5% as they want. Unfortunately, there is little public information on how states do so.

Low percentages of financial assistance to farmers of color also reflects larger issues — centuries of violence and discrimination. This includes the seizure of land from farmers of color, the rejection of financing15 and as in the case of Pembroke Township in Kankakee County, Illinois, tax systems that benefit large landholders at the expense of African Americans who have responsibly stewarded their land for over a century.16

Below is 2020 data from the National Sustainable Agriculture showing statistics related to EQIP and farmers of color in the Midwest. The far left column describes the percentage of EQIP financial assistance that went to farmers of color, whereas the far right column describes the percentage of EQIP contracts that went to farmers of color.

State

|

% of financial assistance to socially disadvantaged (SDA) producers (% of $)

|

% of all principal producers that are NRCS SDA by race

|

% of all principal producers that are NRCS SDA by ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic/Latino/Spanish)

|

% of all EQIP contracts that went to SDA producers

|

|

South Dakota

|

13.58%

|

2%

|

1%

|

13%

|

|

Michigan

|

6.70%

|

1%

|

1%

|

4%

|

|

Missouri

|

3.55%

|

1%

|

1%

|

4%

|

|

Wisconsin

|

3.49%

|

1%

|

1%

|

3%

|

|

North Dakota

|

2.64%

|

1%

|

1%

|

5%

|

|

Minnesota

|

2.50%

|

1%

|

1%

|

3%

|

|

Ohio

|

2.11%

|

0%

|

1%

|

2%

|

|

Kansas

|

1.37%

|

1%

|

1%

|

2%

|

|

Nebraska

|

0.70%

|

3%

|

1%

|

1%

|

|

Iowa

|

0.62%

|

0%

|

1%

|

1%

|

|

Indiana

|

0.60%

|

0%

|

1%

|

1%

|

|

Illinois

|

0.30%

|

0%

|

1%

|

1%

|

|

Source: National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition17

|

As the above data shows, NRCS has a responsibility to make EQIP more accessible to farmers of color, especially those who using agroecological farming practices and have been shut out of funding for decades. Better outreach and funding for EQIP is only part of the solution, as we need a national overhaul of the food and farming system to right centuries of wrong. IATP supports providing more up-front payment options for farmers of color and low-capital farmers, including up to 100% practice cost. The fact that EQIP does not provide 100% cost-share and in most cases acts as a reimbursement program rather than a payment program drives many farmers of color away from EQIP.

Policy Solutions

U.S. President Joe Biden and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack often emphasize the need for agriculture, along with other sectors, to be a part of the solution to the climate crisis, including Secretary Vilsack’s notable address to the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in November 2021.18 While some work has been done to better ensure USDA programs address the climate crisis, reforms to EQIP could take these commitments to the next level.

States such as Kansas serve as a model by funding hundreds of projects directed at soil and water conservation, such as cover crops, conservation crop cover and prescribed grazing. These practices are what EQIP is intended for: helping farmers implement sound environmental practices. Contrast such payments to Minnesota, where just 43 farmers were given an average of $143,000 each to put in waste storage facilities, a practice that is almost solely used by large CAFOs.

As it exists now, while many good conservation projects are funded by EQIP, the program widens many of the economic gaps between big and small farms, as well as between white farmers and farmers of color. In a world where market forces are already creating inequities, Congress and the U.S. Department of Agriculture should use their power to narrow those gaps. We need to both expand investments in conservation programs like EQIP to make them more accessible, but we also need to improve programs like EQIP to make them work better. Some policy changes that could help improve the program’s performance include:

Pay farmers for practices ahead of time, at up to 100% of cost.

- Currently, EQIP is set up as a reimbursement program, with the expectation that farmers pay for the practices on their own, with USDA sending a reimbursement check later. Even with occasional 50% advance payments, this structure can serve as a roadblock for low-capital farmers to be involved in the program. The additional resources needed to pay for 100% cost-share could come from money otherwise used for industrial practices, as well as additional funding from Congress.

Remove harmful industrial practices from EQIP funding eligibility and restore EQIP to its original intent.

- This would require Congress to outline specific practices to remove from funding eligibility in the 2023 Farm Bill. However, state conservationists and STACs could take action earlier by deprioritizing some of these industrial practices.

Improve outreach to farmers of color

- While USDA has made some strides on outreach to farmers of color through successful programs like the High Tunnel System Initiative,19 more work needs to be done to show EQIP’s utility for farmers of color, especially since many states are not fulfilling their 5% set-asides for Socially Disadvantaged Producers.

Prioritize sustainable grazing systems in livestock set asides.

- While some states have done a good job prioritizing sustainable grazing systems, much more needs to be done to direct animal operations toward this model. Additional resources for grazing specialists in local USDA offices would help toward this goal, as laid out in the Grazing Lands Conservation Initiative.20 For some states with few livestock, it might make more sense to remove the 50% livestock requirement altogether.

Ensure that USDA responsibly collects data on who is being served by federal programs.

- As IATP highlighted in Closed Out, current data collection on how USDA programs serve farmers of color is insufficient. While we know how many farmers of each race are being served by EQIP nationwide, NRCS does not break the data down by race at the state level, only by whether a farmer is considered “socially disadvantaged.” Because the needs of Native American farmers differ from the needs of Black farmers, Asian farmers and Hispanic farmers, better data could help target outreach and resources to where it is needed most. This data should be collected down to the county level.

While these policy solutions are by no means the only reforms needed for EQIP to betting align the program toward economic and environmental justice for farmers, they are good first steps.

While federal policy changes can help farmers tremendously in accessing EQIP, state policy matters, too. This is shown by the example of North Dakota. Because it is much harder for factory farms to operate in North Dakota than it is in places like South Dakota, Iowa and Minnesota, there are fewer operations that request assistance in paying for industrial practices. When fewer EQIP dollars are going to factory farms, more money is available for the small and midsize operations that need it most. Federal and state policy can work in concert for sound farm policy or can lead to policy that literally poisons the local farm economy.

Conclusion

In short, while EQIP has done much good across the Midwest, the program as it currently exists too often supports practices that go against the program’s original intent. In a time when farmers are lining up by the thousands to seek help with on-farm conservation, USDA and Congress need to seriously consider whether taxpayer dollars are wisely spent on industrial EQIP practices. As the costs of these industrial practices on the planet become clearer, it becomes less defensible to allow public funds to support them.

While the cost of climate inaction is high, the cost of climate antagonism is higher.

Download the PDF to view the acknowledgements, photo credits and the endnotes.