This blog is part of a series exploring NAFTA and agriculture. The series is based on the larger paper: NAFTA Renegotiation: What’s at stake for farmers, food and the land?

Because NAFTA entered into force around the same time as the formation of the WTO and the 1996 Farm Bill—not to mention the series of free trade agreements that followed—it is difficult to tie precise outcomes in the agriculture sector to NAFTA. But the trends in agriculture post-NAFTA very clearly show the loss of small and medium sized farms, the rapid expansion of CAFOs and contract production in the meat and poultry sector, and the growing power of multinational agribusiness firms across the North American market. Below we explore outcomes and trends in agriculture and food following the passage of NAFTA.

Agricultural trade

NAFTA has dramatically contributed to the integration of North American agricultural markets, according to the USDA.15Integration is when formerly separate markets have combined to form a single market. Final food products, like beef, experience integrated markets as well as raw materials like animal feed.

Agriculture trade among the three countries has expanded considerably, though the U.S. agricultural trade balance with NAFTA partners has fallen with both partners, according to an analysis of government data by the University of Tennessee’s Agricultural Policy Analysis Center (APAC). APAC found that from 1997 through 2014, U.S. overall agricultural trade balance with Canada was a negative $30.4 billion and with Mexico a negative $9.6 billion.16

The top U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico are animal products, grains, oilseeds and sugar, which together made up 79 percent of exports in 2015. Mexico is the top market for U.S. pork, chicken and corn. U.S. corn exports to Mexico more than quadrupled in volume compared to the decade prior to NAFTA.17 Mexico bought about 28 percent of all corn exported from the U.S., $2.5 billion worth, in 2015-16.18

Mexican exports of fruits and vegetables and some animal products to the U.S. also expanded under NAFTA. In the year before NAFTA, the U.S. was largely a net fruit and vegetable exporter, and now is a net importer by a wide margin. Mexico’s annual exports of fruit and vegetables to the U.S. more than tripled by 2013. Mexico and Canada are the largest foreign suppliers of U.S. fruits and vegetables.19

The integration of the North American market is perhaps best understood through meat and poultry production. Between 1993 and 2013, trade between the three countries in animal products increased more than three-fold from $4.6 billion to $15.5 billion.20 U.S. beef exports rose 78 percent by volume since 1993, with Mexico being the number one importer and Canada number four.21 The export of animal feed from the U.S. to Mexico’s pork and poultry industries rose in correlation with increases in Mexican pork and poultry production.

Beef and pork production itself has become much more integrated between the three countries. The U.S. now imports live cattle from Mexico and Canada to finish and process. Mexico has averaged about 1.2 million head of cattle exported to the U.S. for fattening and processing each year since 2000.22 These imports of live cattle have allowed the beef industry to depress the market price for U.S. raised cattle. The result is the reduction of the U.S. cattle herd and loss of U.S. cattle ranchers. According to the Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund (R-CALF), the U.S. has lost 147,000 live cattle producers from 1996-2009.23 Because Mexico and Canada brought a successful case at the WTO to challenge the U.S. mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) rule for beef, consumers in the U.S. do not know where their beef was born and raised.

Canadian hogs are also brought to the U.S. for slaughter. In 2014, the U.S. imported 3.9 million Canadian feeder pigs.24 These pigs, birthed on Canadian farms, were finished and slaughtered in U.S. The pig products are consumed in the U.S. or exported, often to Canada or Mexico.

It is not just animal production that has cross-border integration as part of its business model. For example, cotton is produced in the U.S. and sent to Mexico to be turned into jeans and imported back into the U.S.25 Much of U.S. seed is developed in the U.S. and then sent to Mexico to be “multiplied” or grown in sufficient quantities for sale to U.S. farmers.26

Farmers and ranchers

The integration of agricultural markets has led to a decline in the number of farmers in all three countries. The USDA does not monitor agricultural trade related job loss, and there is no NAFTA Trade Adjustment Assistance program for farmers as there is for some classes of industrial workers. However, USDA data shows a dramatic increase in the number of very large farms and a sharp drop in the number of mid-sized farmers after NAFTA.

From 1992 through 2012 the U.S. lost 245,288, or 22 percent, of small-scale farmers (under $350,000 annual gross farm income) and 6,123, or 5 percent of mid-sized farmers (under $999,999 annual gross farm income). As farmland ownership consolidated in the U.S., large-scale farms ($1 million and over annual gross farm income) increased by 35,066, or 107 percent.27 The number of farms responsible for 50 percent of U.S. agricultural production was cut in half from 1987 through 2012.28

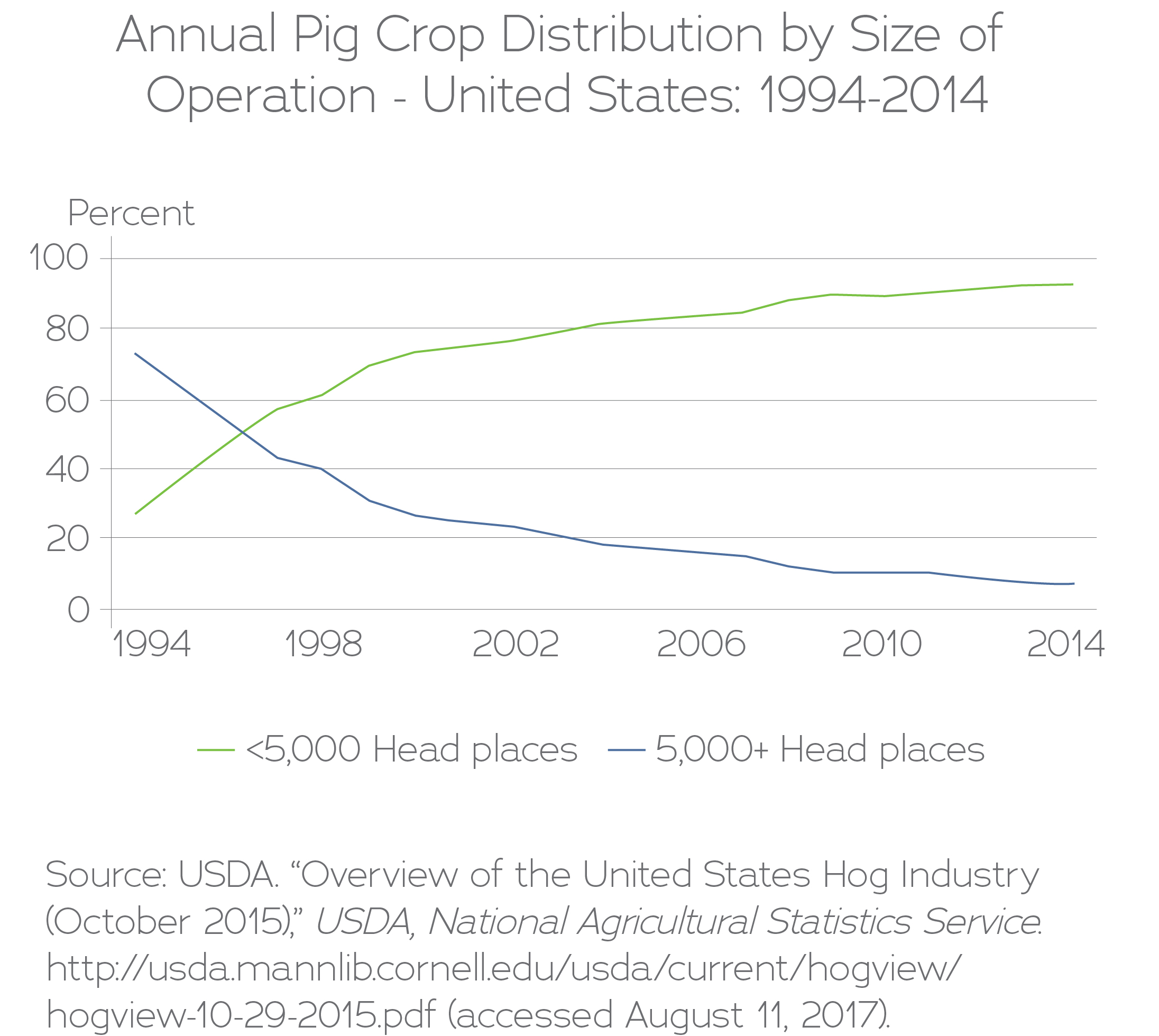

The loss of many U.S. farms during this period, linked to low commodity prices, is also connected to major changes in meat production. The CAFO model depends on cheap animal feed, often sold below the cost of production. In effect, cheap corn and soy, aided by the 1996 Farm Bill, served as a subsidy for CAFO production, according to research by Tufts University’s Global Development and Environment Institute.29 The expansion of factory farms, particularly in poultry and hog production, has led to most of U.S. meat production coming from fewer, big operations. The growth in CAFOs has coincided with the disappearance of independent poultry and pork producers—now nearly all under contract with multinational meat companies like Smithfield and Tyson. Contract farming has been highly criticized for being unfair to producers, burdening them with up front costs, associated debt, and other financial risks, while not paying fair prices to cover those costs.

The dairy industry has also followed the CAFO model. Smaller dairies have been pushed out by lower prices, driven largely by over-production from increasingly large dairy CAFOs.30 One of the driving motivations behind the dairy industry’s active engagement in the TPP, and now NAFTA, is to tear down Canada’s supply management program in an effort to absorb excess milk production from U.S. dairy CAFOs.

Farmers and ranchers in Mexico and Canada have also been hurt by NAFTA. Based on Mexican Census data, Tufts University researcher Tim Wise estimates that more than two million Mexicans left agriculture in the wake of NAFTA’s flood of imports, or as many as one-quarter of the farming population.31 And over the last 30 years, Canada has lost one-third of its farm families. Today, there are just under 200,000 Canadian farmers.32

Food system workers

The U.S. food system is deeply dependent on immigrant labor—particularly fruit, vegetable and dairy production and meat processing. According to the Farm Bureau, U.S. agriculture relies on an estimated 1.5 to two million farm workers, with 50 to 70 percent of those unauthorized.33

While proponents of NAFTA argued that it would improve the economic conditions in Mexico and reduce the movement of immigrants from Mexico to the U.S., the exact opposite occurred (as critics like IATP predicted34). Mexico’s poverty rate in 2014 was higher than its poverty rate in 1994, and real (inflation-adjusted) wages were almost the same in 2014 as in 1994.35 From 1994 through 2009, Mexican emigration to the U.S. more than doubled. Since 2009 (directly following the financial crisis), that trend has started to reverse with more Mexicans returning to Mexico from the U.S. than entering the U.S.36

The reduction of the U.S. cattle herd has also led to the loss of beef processing jobs since NAFTA. According to the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, 50 plants have closed since taking out 52,695 in daily cattle kill capacity after the passage of NAFTA.37 Meat processing in the U.S. had already begun a major reorganization in the 1970s and 1980s, transitioning to fewer, much larger meat packing plants, and moving those packing plants to rural areas where union organizing was more difficult. Simultaneously, poultry processing took off largely in anti-union southern states—creating low-cost competition for the beef and pork industries. The availability of immigrant labor, including from Mexico, aided in the meat industry’s efforts to break the unions and keep labor costs low.

U.S. factory farms, particularly dairy CAFOs, are deeply reliant on new immigrant labor, often from Mexico.38 Working conditions are often difficult and new immigrants, often undocumented, have few legal protections. Latino immigrant workers in the New York dairy industry released a report this summer documenting poor treatment, including on-the-job injuries, intimidation, poor housing and long hours for low pay.39

The Trump Administration’s aggressive anti-immigrant policies, from advocating for a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to making it more difficult for temporary agricultural workers to enter the U.S., are causing disruptions in agricultural operations across the country. A growing number of U.S. farm operations (primarily fruit, vegetable and dairy) face worker shortages due to the immigration crackdown.40 The fruit and vegetable industry has testified before Congress calling for action to allow the entry of more workers.41 The dairy industry is particularly concerned with the Trump Administration’s aggressive anti-immigrant policies, warning that the price of milk could skyrocket without low cost, immigrant workers.42

While immigration rules are not explicitly included in NAFTA, there is little disagreement that the trade agreement contributed to rising immigration, and that U.S. agribusiness has benefitted greatly from that development.

Agribusiness market share

Since NAFTA, there has been a dramatic increase in agribusiness market share concentration in nearly all sectors including seeds, fertilizer, meat and crop production. Agribusiness concentration levels in U.S. agriculture are high and rising—and as competition declines, farmers and ranchers are vulnerable to agribusiness efforts to depress prices, according to a recent USDA report.43 In addition, it can be difficult for farmers and ranchers to gather market information, i.e., price transparency and price discovery—in highly concentrated markets.

“One of the major consequences of NAFTA was the consolidation and restructuring of the agri-food system on the continent,” writes Dr. William Heffernan of the University of Missouri. “This has led to profound impacts on firms, employees and communities even in the United States.”44

The top 10 companies exporting foodstuffs from the U.S. to Mexico include grain companies Bartlett Grain, ADM, Cargill and CHS, as well as meat companies such as Tyson Foods and JBS, according to Panjiva, a trade data company. The top 10 companies shipping north include Driscoll’s, a berry grower; Grupo Viz, a Mexican meat supplier; Mondelez, the U.S. snacks company; and Mission Produce, an avocado producer.45

Many of the global meat giants have operations throughout North America. For example, Smithfield has pork production joint ventures in Mexico with Granjas Carroll de Mexico and Norson. Brazillian-owned JBS’s poultry division, Pilgrim’s De Mexico, has multiple locations throughout Mexico. JBS, currently embroiled in a major bribery and food safety scandal, is also deeply invested in beef processing in Canada. Cargill, the meat and animal feed giant, has 30 facilities in 13 Mexican states and extensive meat and grain investments in Canada.

Smithfield, the world’s largest pork producer now owned by the Chinese WH Group, benefited in particular from NAFTA. An analysis by Tufts University’s Global Development and Environment Institute concluded that a glut of cheap animal feed resulting from the 1996 Farm Bill, allowed Smithfield to export pork to NAFTA countries at below the cost of production prices. The company then benefited from NAFTA’s investment rules to expand its Mexican operations. The diminishing number of farmers in Mexico caused by NAFTA also provided access to cheap labor.46

When President Trump threatened to pull out of NAFTA, it immediately kicked their lobbying into high gear to reach the White House with their concerns. At the sole NAFTA public hearing held by the U.S. Trade Representative, Cargill emphasized a cautionary approach “We appreciate the Administration’s guiding principle of ‘do no harm’ for the NAFTA renegotiations.”47 In comments to the USTR, JBS USA also urged the USTR to “first, preserve current market access and the conditions that support integrated value chains, including all tariff and duty preferences and rules that allow U.S. businesses to compete in the North American market.”48 And the U.S. Meat Export Federation warned, “any erosion in the market access terms contained in the existing NAFTA agreement would be highly detrimental for farmers, feedlots, meatpacking plants, and exporters.”49

Food safety

Just as trade agreements have shaped U.S. farm policy to benefit agribusiness, so have trade deals contributed to the weakening of U.S. food safety rules to benefit food companies. The food safety, plant and animal disease provisions in NAFTA, known as Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), and soon thereafter the establishment of the WTO SPS rules, helped usher in a new era of food safety de-regulation. NAFTA established that Mexico and Canada food safety regulations did not have to be “equal” (or the same as) to U.S. regulations, but rather the more difficult to interpret and verify “equivalent.” The definition of “equivalence” was not part of NAFTA – nor was the requirement that independent government inspectors, rather than meat company staff, do the actual inspecting.

Not only did NAFTA establish a food safety template for future trade deals in which trade concerns were given priority over consumer health, it also helped propel efforts to deregulate and privatize food safety inspection in the U.S.

As food safety expert and former IATP board member Rod Leonard has written, rules set at NAFTA and at the international standards body Codex, were used in 1996 to push U.S. food safety standards, particularly for meat and poultry, toward greater company controlled inspection. “As the global norm in food safety, `equivalence’ was intended to start the race to the bottom of food safety standards globally,” Leonard wrote.50

Earlier this year, USDA auditors found that the meat inspection system for most meat processing plants (including JBS and Cargill beef operations) in Canada was not “equivalent” to U.S. standards. Canada has moved toward a privatized inspection system, with the companies taking on more responsibility, according to Food and Water Watch.51

The rise of food imports under NAFTA has increased pressure on food safety inspectors at the Food and Drug Administration and the USDA. According to Public Citizen, the FDA physically inspects only 1.8 percent of food imports it regulates (vegetables, fruit, seafood, grain, dairy and animal feed); and the USDA only 8.5 percent of beef, pork and chicken that is imported.52

The need for greater oversight of food imports has been severely undermined by inadequate funding of food safety inspection programs. In 2011, President Obama signed into law the Food Safety Modernization Act, but earlier in 2017, Congress appropriated only about half the resources needed to implement the law. A GAO report found that the FDA could not meet the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) mandate for inspections of foreign importers due to lack of resources.53 According to food safety expert Bill Marler, “FDA is inspecting only about 2,500 foreign food suppliers today. The FDA should be inspecting nearly 20,000.”54

NAFTA also allowed for the regionalization of food safety standards to facilitate trade in meat. This regionalization was particularly important in cases of animal disease outbreaks. For example, when localized outbreaks of Avian influenza hit specific counties in specific U.S. states, poultry trade with Mexico was allowed to continue uninterrupted, with the exception of those states.55

NAFTA’s SPS rules have been tested in recent years with the development of animal diseases in multiple NAFTA countries. These diseases may be linked to high levels of market integration. In 2009, a new flu strain (a mixture of swine, human and avian flues) emerged out of the state of Vera Cruz Mexico, an area heavily populated by hog CAFOs, later spreading into parts of the U.S. There is some evidence that the initial strains of the flu emerged from North Carolina—home to a high density of hog CAFOs—leaving pathogen expert Rob Wallace to dub it the “NAFTA flu.”56 In 2014, a deadly porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDv) in piglets hit both U.S. and Mexico pork production,57 and this year the virus hit Canada.58 As the U.S. has struggled with outbreaks of various strains of avian flu in confined poultry facilities throughout the country, so has Mexico in Veracruz, Puebla and Jalisco states, as has Ontario, Canada.59,60

Health

The adverse health effects of rising obesity rates have been well documented in the U.S.61 Similar rising obesity rates in both Mexico and Canada have been linked to NAFTA. In the case of Mexico, increases in imports of sweeteners, processed foods and meats have translated into increased consumption of snack foods, processed dairy products and soft drinks.62 Research published this year from Canada reached similar conclusions.63

Aside from increased imports, NAFTA’s investment provisions helped facilitate the investment of U.S. processed food companies in both Mexico and Canada. Food sales associated with U.S. investment in Canada and Mexico are now substantial. In 2012, majority owned affiliates of U.S. multinational food companies had sales of $32.4 billion in Canada and $13.8 billion in Mexico—these sales were 90 percent larger than the value of U.S. processed food exports to Canada and Mexico.64

Climate change

While greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions overall increased in all three countries during the NAFTA years, GHGs specifically tied to agriculture varied. In the U.S., agriculture-related GHGs increased from 1990 to 2015 by eight percent. The Environmental Protection Agency has identified the increase in CAFOs as a primary cause: “One driver for this increase has been the 64 percent growth in combined CH4 and N2O emissions from livestock manure management systems.”65 Agriculture-related GHGs increased slightly in Mexico from 1990 to 2015, also tied to the livestock industry.66 Agriculture-related emissions have remained largely flat over the last decade in Canada.67