Download the print copy here.

Overview

The re-negotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the U.S., Mexico and Canada begins on August 16, and there is much at stake for farmers and rural communities in all three countries. Despite promised gains for farmers, NAFTA’s benefits over the last 23 years have gone primarily to multinational agribusiness firms. NAFTA is about much more than trade. It set rules on investment, farm exports, food safety, access to seeds, and markets. NAFTA, combined with the formation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the 1996 Farm Bill, led the charge to greater consolidation among agribusiness firms, the loss of many small and mid-sized farms and independent ranchers, the rapid growth of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and further corporate control of animal production through often unfair, restrictive contracts with producers. The Trump administration’s negotiating objectives reflect relatively small tweaks to NAFTA, while adopting deregulatory elements of the defeated Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Family farm groups have called for the existing NAFTA to be scrapped and propose a fundamentally new agreement with a goal of improving the lives of family farmers and rural communities in all three countries.

What is NAFTA?

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was agreed to by the U.S., Mexico and Canada in 1992, ratified by the U.S. Congress in 1993, and became enforceable in 1994. The Agreement has 22 chapters, grouped into eight sections.1 Those sections cover trade rules on a variety of goods, including textiles, agriculture and food safety, and energy; technical standards for traded goods; government procurement; protection for investors and trade in services; intellectual property; notification of new laws and how to handle trade disputes.

NAFTA was the first of its kind in several ways: the first trade agreement among countries at very different levels of economic development; the first to include controversial private arbitration panels that allow foreign corporations to sue governments to challenge actions that impede their potential future profits; and the first trade agreement to include side agreements on labor and environment. It was the template for the U.S.-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement, and the defeated Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), among others, as well as dozens of other agreements negotiated by Canada and Mexico. Each of the trade deals that followed included additional elements that strengthened corporations’ ability to move production and investments in all participating countries.

What promises were made to farmers?

During the NAFTA debate in the early 1990s, U.S. farmers and ranchers were promised that they would export their way to prosperity but that didn’t happen. A U.S. Department of Agriculture fact sheet at the time pledged that NAFTA would “boost incomes in Mexico and increase demand for a greater volume and variety of food and feed products” from U.S. farmers.2 The USDA fact sheet vowed that U.S. farmers would gain from “higher agricultural export prices” among other benefits. An International Trade Commission analysis advising Congress in 1993 downplayed the impact NAFTA would have on agriculture, predicting only “a minimal effect on overall U.S. agricultural production and employment,” aside from some increases in grain and meat exports, and a slight increase in fruit and vegetable imports.3 The same ITC report predicted that U.S. Midwest soy and corn farmers would benefit from increased exports to Mexico.

The General Accounting Office (now Government Accountability Office) concluded that NAFTA would “reduce unauthorized Mexican migration to the United States in the long run...”4 President Bill Clinton made a similar argument at the time stating: “By raising the incomes of Mexicans, which this (NAFTA) will do, they’ll be able to buy more of our products and there will be much less pressure on them to come to this country in the form of illegal immigration.”5 Conservative think tanks like the Peterson Institute for International Economics joined in the NAFTA cheerleading through opinion pieces in the media that exclaimed “Everybody Wins,” and predicted strong long-term growth in Mexico’s per capita income with associated declines in immigration to the U.S.6

These false promises, supported by a compliant media, gave Congressional backers the fuel they needed to narrowly pass NAFTA in 1993. Whether economic gains for farmers or reduced migration from Mexico, NAFTA’s promises of prosperity have proven to be empty ones.

What parts of NAFTA relate to food and agriculture?

Phasing out of tariffs

NAFTA’s Chapter 3 on National Treatment and Market Access set a schedule to phase out tariffs on most agricultural goods traded among the three countries, finally coming into full force in 2008. Tariffs on some goods, such as imports of corn and soybeans to Mexico, were phased out over 15 years—although Mexico accelerated that timetable under pressure from the U.S.7 (Previously, Mexico had charged an average tariff of 11 percent on imports of agricultural goods.) U.S. agricultural tariffs were for the most part already low. Many Mexican farm goods entered the U.S. duty-free prior to NAFTA under the Generalized System of Preferences, which gives tariff preferences to developing countries. Tariffs on U.S.-Canada trade for most agricultural goods had already been eliminated under the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement, which formally came into force in 1989.8

Some exceptions to the free flow of agricultural goods were established under NAFTA. Canada retained the right to maintain its dairy, poultry and egg supply management programs, which support fair prices for Canadian producers and consumers. These programs include some limits on imports and high tariffs for those products. NAFTA also includes a side agreement that expands the volume of Mexican sugar imports into the U.S., while still protecting the U.S. sugar program, which also functions essentially as a supply management program.

Food safety

The Agriculture and Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Chapter of NAFTA (Chapter 7) sets broad rules for domestic support, eliminates export subsidies, and establishes a mechanism to handle trade disputes. The second part of the chapter focuses on food safety rules, and ensuring that those rules will not act as a barrier to trade. Equivalency agreements between the three countries streamlined inspections of foods crossing borders, and put pressure on inspectors and food safety agencies to facilitate trade. NAFTA also established an ongoing food safety standards committee to settle disputes between the three countries.

Special rights for foreign corporations

NAFTA was the first free trade agreement to establish special legal rights for foreign corporations. NAFTA’s Chapter 11 established the Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS), which grants foreign investors the right to sue local or national governments over measures that affect their real or potential profits on existing or planned investments.9 This ground-breaking corporate privilege provision has been replicated in nearly every ensuing U.S. trade deal. There have been only a few agricultural ISDS disputes under NAFTA. Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland and Corn Products International have all successfully sued Mexico and won multimillion dollar settlements, for the country’s tariffs on high fructose corn syrup.

Intellectual property

NAFTA’s Chapter 17 was the first free trade chapter to include meaningful rules on intellectual property rights (IPR) for seeds and other biological resources. NAFTA built upon on-going international negotiations that ultimately created the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement in the WTO. The NAFTA IPR chapter references the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants 1978 (UPOV Convention 1978), and the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants 1991 (UPOV Convention 1991)—which place restrictions on farmers’ and researchers’ rights to save and share seeds.10 While all NAFTA parties were expected to either be part of these Conventions, or join the Conventions soon after, Mexico never did join UPOV 1991—an issue that re-surfaced during the TPP negotiations, and will likely be raised again during NAFTA renegotiations. During the negotiation of Chapter 17, IATP was part of a coalition that criticized the legal and economic disruption by patent holders of traditional agricultural practices, such as the planting of saved seeds and cross-breeding of shared seeds.11

What is the relationship between NAFTA, the World Trade Organization and the Farm Bill?

The rules set in NAFTA (1994), the WTO (1995) and the 1996 Farm Bill are mutually reinforcing. The WTO set a foundation of international trade rules for more than 160 countries. The WTO’s Agreement on Agriculture set international trade rules on agriculture policy, including the types of farm programs that are allowed (non-trade distorting), tariff levels on agricultural goods and how those tariffs may be applied. If NAFTA were eliminated, the trade rules set at the WTO would be the fallback.

The 1996 Farm Bill passed by Congress was designed to comply with trade rules agreed to in NAFTA and the WTO. It stripped away the final remnants of U.S. supply management programs (with sugar the exception), which had intentionally limited production for the purpose of ensuring fair prices to farmers. The 1996 bill was given a slick market-friendly name, “Freedom to Farm” and its elimination of supply management was sold to farmers as necessary for expanding U.S. export markets. That expanded access, the bill’s supporters claimed, would itself ensure fair prices to farmers. This did not turn out to be the case. “Freedom to Farm has really positioned the U.S. very well to take advantage of the opportunities in the world market,” said a Cargill executive shortly after the bill was passed.12

Shortly following the passage of the 1996 Farm Bill, U.S. farm prices predictably plunged following the expanded production—and tens of millions of dollars of emergency payments were needed to prevent many farmers from losing their farms.13 Those low prices, coupled with NAFTA’s and the WTO’s requirements to lower tariffs, facilitated the rapid growth of agricultural export dumping (exporting below the cost of production) by U.S. agribusiness over the next decade.14 Many Mexican farmers who were particularly hard hit by a flood of U.S. corn exports eventually emigrated to the U.S. to work on farms and in meat packing plants. In 2002, the Farm Bill took steps to convert the emergency payments for farmers into commodity program farm subsidies. These programs, further adapted in ensuing Farm Bills, support farmers when prices drop due to over-production, and continue today in the form of revenue-insurance programs.

What are the outcomes of NAFTA?

Because NAFTA entered into force around the same time as the formation of the WTO and the 1996 Farm Bill—not to mention the series of free trade agreements that followed—it is difficult to tie precise outcomes in the agriculture sector to NAFTA. But the trends in agriculture post-NAFTA very clearly show the loss of small and medium sized farms, the rapid expansion of CAFOs and contract production in the meat and poultry sector, and the growing power of multinational agribusiness firms across the North American market. Below we explore outcomes and trends in agriculture and food following the passage of NAFTA.

Agricultural trade

NAFTA has dramatically contributed to the integration of North American agricultural markets, according to the USDA.15 Integration is when formerly separate markets have combined to form a single market. Final food products, like beef, experience integrated markets as well as raw materials like animal feed.

Agriculture trade among the three countries has expanded considerably, though the U.S. agricultural trade balance with NAFTA partners has fallen with both partners, according to an analysis of government data by the University of Tennessee’s Agricultural Policy Analysis Center (APAC). APAC found that from 1997 through 2014, U.S. overall agricultural trade balance with Canada was a negative $30.4 billion and with Mexico a negative $9.6 billion.16

The top U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico are animal products, grains, oilseeds and sugar, which together made up 79 percent of exports in 2015. Mexico is the top market for U.S. pork, chicken and corn. U.S. corn exports to Mexico more than quadrupled in volume compared to the decade prior to NAFTA.17 Mexico bought about 28 percent of all corn exported from the U.S., $2.5 billion worth, in 2015-16.18

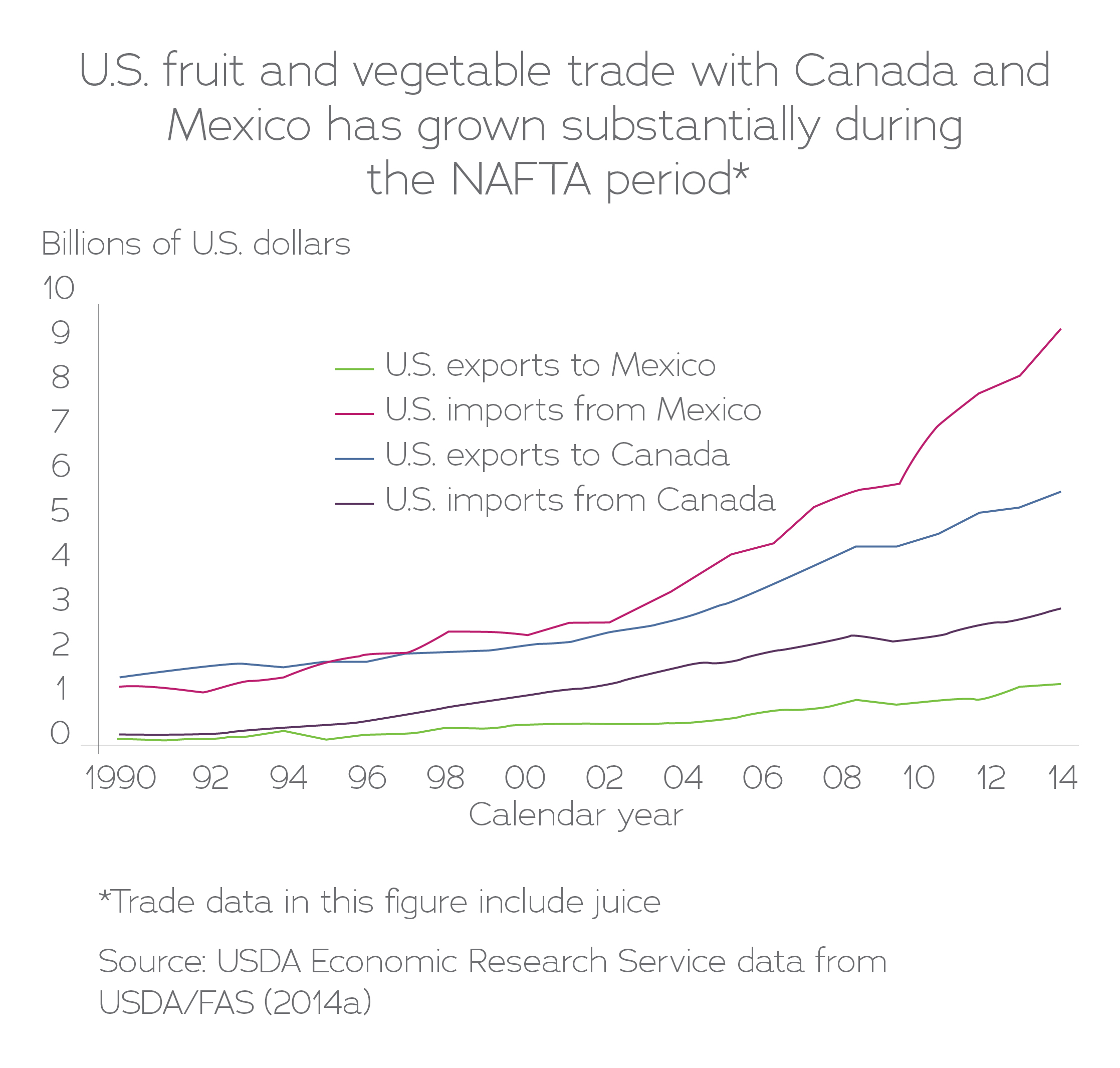

Mexican exports of fruits and vegetables and some animal products to the U.S. also expanded under NAFTA. In the year before NAFTA, the U.S. was largely a net fruit and vegetable exporter, and now is a net importer by a wide margin. Mexico’s annual exports of fruit and vegetables to the U.S. more than tripled by 2013. Mexico and Canada are the largest foreign suppliers of U.S. fruits and vegetables.19

The integration of the North American market is perhaps best understood through meat and poultry production. Between 1993 and 2013, trade between the three countries in animal products increased more than three-fold from $4.6 billion to $15.5 billion.20 U.S. beef exports rose 78 percent by volume since 1993, with Mexico being the number one importer and Canada number four.21 The export of animal feed from the U.S. to Mexico’s pork and poultry industries rose in correlation with increases in Mexican pork and poultry production.

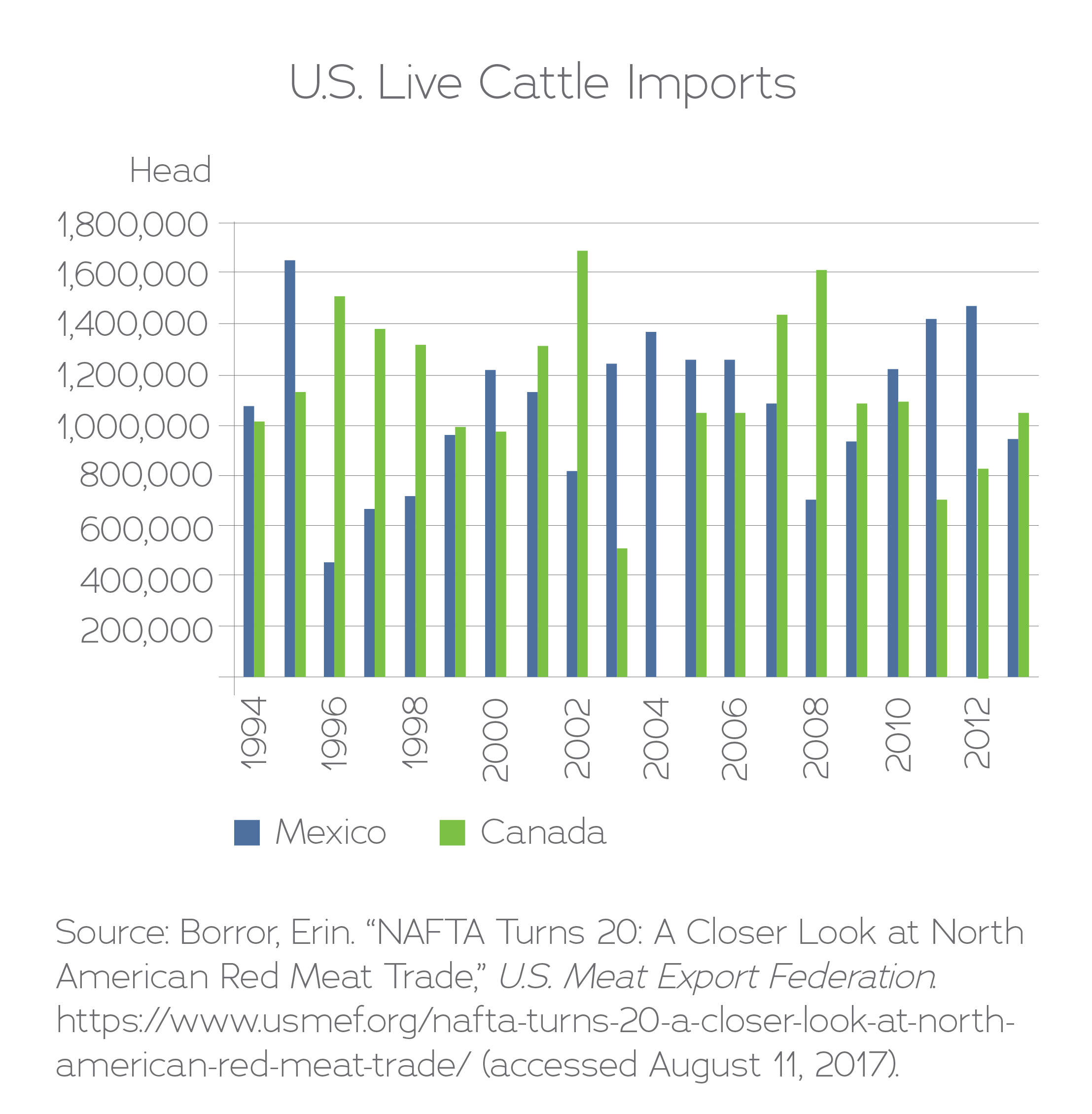

Beef and pork production itself has become much more integrated between the three countries. The U.S. now imports live cattle from Mexico and Canada to finish and process. Mexico has averaged about 1.2 million head of cattle exported to the U.S. for fattening and processing each year since 2000.22 These imports of live cattle have allowed the beef industry to depress the market price for U.S. raised cattle. The result is the reduction of the U.S. cattle herd and loss of U.S. cattle ranchers. According to the Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund (R-CALF), the U.S. has lost 147,000 live cattle producers from 1996-2009.23 Because Mexico and Canada brought a successful case at the WTO to challenge the U.S. mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) rule for beef, consumers in the U.S. do not know where their beef was born and raised.

Canadian hogs are also brought to the U.S. for slaughter. In 2014, the U.S. imported 3.9 million Canadian feeder pigs.24 These pigs, birthed on Canadian farms, were finished and slaughtered in U.S. The pig products are consumed in the U.S. or exported, often to Canada or Mexico.

It is not just animal production that has cross-border integration as part of its business model. For example, cotton is produced in the U.S. and sent to Mexico to be turned into jeans and imported back into the U.S.25 Much of U.S. seed is developed in the U.S. and then sent to Mexico to be “multiplied” or grown in sufficient quantities for sale to U.S. farmers.26

Farmers and ranchers

The integration of agricultural markets has led to a decline in the number of farmers in all three countries. The USDA does not monitor agricultural trade related job loss, and there is no NAFTA Trade Adjustment Assistance program for farmers as there is for some classes of industrial workers. However, USDA data shows a dramatic increase in the number of very large farms and a sharp drop in the number of mid-sized farmers after NAFTA.

From 1992 through 2012 the U.S. lost 245,288, or 22 percent, of small-scale farmers (under $350,000 annual gross farm income) and 6,123, or 5 percent of mid-sized farmers (under $999,999 annual gross farm income). As farmland ownership consolidated in the U.S., large-scale farms ($1 million and over annual gross farm income) increased by 35,066, or 107 percent.27 The number of farms responsible for 50 percent of U.S. agricultural production was cut in half from 1987 through 2012.28

The loss of many U.S. farms during this period, linked to low commodity prices, is also connected to major changes in meat production. The CAFO model depends on cheap animal feed, often sold below the cost of production. In effect, cheap corn and soy, aided by the 1996 Farm Bill, served as a subsidy for CAFO production, according to research by Tufts University’s Global Development and Environment Institute.29 The expansion of factory farms, particularly in poultry and hog production, has led to most of U.S. meat production coming from fewer, big operations. The growth in CAFOs has coincided with the disappearance of independent poultry and pork producers—now nearly all under contract with multinational meat companies like Smithfield and Tyson. Contract farming has been highly criticized for being unfair to producers, burdening them with up front costs, associated debt, and other financial risks, while not paying fair prices to cover those costs.

The dairy industry has also followed the CAFO model. Smaller dairies have been pushed out by lower prices, driven largely by over-production from increasingly large dairy CAFOs.30 One of the driving motivations behind the dairy industry’s active engagement in the TPP, and now NAFTA, is to tear down Canada’s supply management program in an effort to absorb excess milk production from U.S. dairy CAFOs.

Farmers and ranchers in Mexico and Canada have also been hurt by NAFTA. Based on Mexican Census data, Tufts University researcher Tim Wise estimates that more than two million Mexicans left agriculture in the wake of NAFTA’s flood of imports, or as many as one-quarter of the farming population.31 And over the last 30 years, Canada has lost one-third of its farm families. Today, there are just under 200,000 Canadian farmers.32

Food system workers

The U.S. food system is deeply dependent on immigrant labor—particularly fruit, vegetable and dairy production and meat processing. According to the Farm Bureau, U.S. agriculture relies on an estimated 1.5 to two million farm workers, with 50 to 70 percent of those unauthorized.33

While proponents of NAFTA argued that it would improve the economic conditions in Mexico and reduce the movement of immigrants from Mexico to the U.S., the exact opposite occurred (as critics like IATP predicted34). Mexico’s poverty rate in 2014 was higher than its poverty rate in 1994, and real (inflation-adjusted) wages were almost the same in 2014 as in 1994.35 From 1994 through 2009, Mexican emigration to the U.S. more than doubled. Since 2009 (directly following the financial crisis), that trend has started to reverse with more Mexicans returning to Mexico from the U.S. than entering the U.S.36

The reduction of the U.S. cattle herd has also led to the loss of beef processing jobs since NAFTA. According to the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, 50 plants have closed since taking out 52,695 in daily cattle kill capacity after the passage of NAFTA.37 Meat processing in the U.S. had already begun a major reorganization in the 1970s and 1980s, transitioning to fewer, much larger meat packing plants, and moving those packing plants to rural areas where union organizing was more difficult. Simultaneously, poultry processing took off largely in anti-union southern states—creating low-cost competition for the beef and pork industries. The availability of immigrant labor, including from Mexico, aided in the meat industry’s efforts to break the unions and keep labor costs low.

U.S. factory farms, particularly dairy CAFOs, are deeply reliant on new immigrant labor, often from Mexico.38 Working conditions are often difficult and new immigrants, often undocumented, have few legal protections. Latino immigrant workers in the New York dairy industry released a report this summer documenting poor treatment, including on-the-job injuries, intimidation, poor housing and long hours for low pay.39

The Trump Administration’s aggressive anti-immigrant policies, from advocating for a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to making it more difficult for temporary agricultural workers to enter the U.S., are causing disruptions in agricultural operations across the country. A growing number of U.S. farm operations (primarily fruit, vegetable and dairy) face worker shortages due to the immigration crackdown.40 The fruit and vegetable industry has testified before Congress calling for action to allow the entry of more workers.41 The dairy industry is particularly concerned with the Trump Administration’s aggressive anti-immigrant policies, warning that the price of milk could skyrocket without low cost, immigrant workers.42

While immigration rules are not explicitly included in NAFTA, there is little disagreement that the trade agreement contributed to rising immigration, and that U.S. agribusiness has benefitted greatly from that development.

Agribusiness market share

Since NAFTA, there has been a dramatic increase in agribusiness market share concentration in nearly all sectors including seeds, fertilizer, meat and crop production. Agribusiness concentration levels in U.S. agriculture are high and rising—and as competition declines, farmers and ranchers are vulnerable to agribusiness efforts to depress prices, according to a recent USDA report.43 In addition, it can be difficult for farmers and ranchers to gather market information, i.e., price transparency and price discovery—in highly concentrated markets.

“One of the major consequences of NAFTA was the consolidation and restructuring of the agri-food system on the continent,” writes Dr. William Heffernan of the University of Missouri. “This has led to profound impacts on firms, employees and communities even in the United States.”44

The top 10 companies exporting foodstuffs from the U.S. to Mexico include grain companies Bartlett Grain, ADM, Cargill and CHS, as well as meat companies such as Tyson Foods and JBS, according to Panjiva, a trade data company. The top 10 companies shipping north include Driscoll’s, a berry grower; Grupo Viz, a Mexican meat supplier; Mondelez, the U.S. snacks company; and Mission Produce, an avocado producer.45

Many of the global meat giants have operations throughout North America. For example, Smithfield has pork production joint ventures in Mexico with Granjas Carroll de Mexico and Norson. Brazillian-owned JBS’s poultry division, Pilgrim’s De Mexico, has multiple locations throughout Mexico. JBS, currently embroiled in a major bribery and food safety scandal, is also deeply invested in beef processing in Canada. Cargill, the meat and animal feed giant, has 30 facilities in 13 Mexican states and extensive meat and grain investments in Canada.

Smithfield, the world’s largest pork producer now owned by the Chinese WH Group, benefited in particular from NAFTA. An analysis by Tufts University’s Global Development and Environment Institute concluded that a glut of cheap animal feed resulting from the 1996 Farm Bill, allowed Smithfield to export pork to NAFTA countries at below the cost of production prices. The company then benefited from NAFTA’s investment rules to expand its Mexican operations. The diminishing number of farmers in Mexico caused by NAFTA also provided access to cheap labor.46

When President Trump threatened to pull out of NAFTA, it immediately kicked their lobbying into high gear to reach the White House with their concerns. At the sole NAFTA public hearing held by the U.S. Trade Representative, Cargill emphasized a cautionary approach “We appreciate the Administration’s guiding principle of ‘do no harm’ for the NAFTA renegotiations.”47 In comments to the USTR, JBS USA also urged the USTR to “first, preserve current market access and the conditions that support integrated value chains, including all tariff and duty preferences and rules that allow U.S. businesses to compete in the North American market.”48 And the U.S. Meat Export Federation warned, “any erosion in the market access terms contained in the existing NAFTA agreement would be highly detrimental for farmers, feedlots, meatpacking plants, and exporters.”49

Food safety

Just as trade agreements have shaped U.S. farm policy to benefit agribusiness, so have trade deals contributed to the weakening of U.S. food safety rules to benefit food companies. The food safety, plant and animal disease provisions in NAFTA, known as Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), and soon thereafter the establishment of the WTO SPS rules, helped usher in a new era of food safety de-regulation. NAFTA established that Mexico and Canada food safety regulations did not have to be “equal” (or the same as) to U.S. regulations, but rather the more difficult to interpret and verify “equivalent.” The definition of “equivalence” was not part of NAFTA – nor was the requirement that independent government inspectors, rather than meat company staff, do the actual inspecting.

Not only did NAFTA establish a food safety template for future trade deals in which trade concerns were given priority over consumer health, it also helped propel efforts to deregulate and privatize food safety inspection in the U.S.

As food safety expert and former IATP board member Rod Leonard has written, rules set at NAFTA and at the international standards body Codex, were used in 1996 to push U.S. food safety standards, particularly for meat and poultry, toward greater company controlled inspection. “As the global norm in food safety, `equivalence’ was intended to start the race to the bottom of food safety standards globally,” Leonard wrote.50

Earlier this year, USDA auditors found that the meat inspection system for most meat processing plants (including JBS and Cargill beef operations) in Canada was not “equivalent” to U.S. standards. Canada has moved toward a privatized inspection system, with the companies taking on more responsibility, according to Food and Water Watch.51

The rise of food imports under NAFTA has increased pressure on food safety inspectors at the Food and Drug Administration and the USDA. According to Public Citizen, the FDA physically inspects only 1.8 percent of food imports it regulates (vegetables, fruit, seafood, grain, dairy and animal feed); and the USDA only 8.5 percent of beef, pork and chicken that is imported.52

The need for greater oversight of food imports has been severely undermined by inadequate funding of food safety inspection programs. In 2011, President Obama signed into law the Food Safety Modernization Act, but earlier in 2017, Congress appropriated only about half the resources needed to implement the law. A GAO report found that the FDA could not meet the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) mandate for inspections of foreign importers due to lack of resources.53 According to food safety expert Bill Marler, “FDA is inspecting only about 2,500 foreign food suppliers today. The FDA should be inspecting nearly 20,000.”54

NAFTA also allowed for the regionalization of food safety standards to facilitate trade in meat. This regionalization was particularly important in cases of animal disease outbreaks. For example, when localized outbreaks of Avian influenza hit specific counties in specific U.S. states, poultry trade with Mexico was allowed to continue uninterrupted, with the exception of those states.55

NAFTA’s SPS rules have been tested in recent years with the development of animal diseases in multiple NAFTA countries. These diseases may be linked to high levels of market integration. In 2009, a new flu strain (a mixture of swine, human and avian flues) emerged out of the state of Vera Cruz Mexico, an area heavily populated by hog CAFOs, later spreading into parts of the U.S. There is some evidence that the initial strains of the flu emerged from North Carolina—home to a high density of hog CAFOs—leaving pathogen expert Rob Wallace to dub it the “NAFTA flu.”56 In 2014, a deadly porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDv) in piglets hit both U.S. and Mexico pork production,57 and this year the virus hit Canada.58 As the U.S. has struggled with outbreaks of various strains of avian flu in confined poultry facilities throughout the country, so has Mexico in Veracruz, Puebla and Jalisco states, as has Ontario, Canada.59,60

Health

The adverse health effects of rising obesity rates have been well documented in the U.S.61 Similar rising obesity rates in both Mexico and Canada have been linked to NAFTA. In the case of Mexico, increases in imports of sweeteners, processed foods and meats have translated into increased consumption of snack foods, processed dairy products and soft drinks.62 Research published this year from Canada reached similar conclusions.63

Aside from increased imports, NAFTA’s investment provisions helped facilitate the investment of U.S. processed food companies in both Mexico and Canada. Food sales associated with U.S. investment in Canada and Mexico are now substantial. In 2012, majority owned affiliates of U.S. multinational food companies had sales of $32.4 billion in Canada and $13.8 billion in Mexico—these sales were 90 percent larger than the value of U.S. processed food exports to Canada and Mexico.64

Climate change

While greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions overall increased in all three countries during the NAFTA years, GHGs specifically tied to agriculture varied. In the U.S., agriculture-related GHGs increased from 1990 to 2015 by eight percent. The Environmental Protection Agency has identified the increase in CAFOs as a primary cause: “One driver for this increase has been the 64 percent growth in combined CH4 and N2O emissions from livestock manure management systems.”65 Agriculture-related GHGs increased slightly in Mexico from 1990 to 2015, also tied to the livestock industry.66 Agriculture-related emissions have remained largely flat over the last decade in Canada.67

What is the process for renegotiating NAFTA?

The President and the executive branch have the authority to negotiate with foreign countries, but Congress must ratify those agreements. The Trump administration must first give Congress a 90-day notice that it will begin NAFTA renegotiation. As part of that notice, the administration must outline its negotiating objectives. Those objectives must also be consistent with trade objectives outlined by Congress in Trade Promotion Authority legislation (also known as Fast Track), which is in effect until July 1, 2021.

In July 2017, President Trump announced his negotiating objectives for NAFTA. The objectives were quite vague, and followed very closely the trade objectives previously outlined under the Trade Promotion Authority legislation. For agriculture, the objectives emphasize the need to “maintain existing reciprocal duty free market access,” expand market access by reducing any remaining tariffs, and promote “greater regulatory compatibility.”68 There has been little explanation from the Trump Administration on how it would achieve these goals.

The first round of NAFTA negotiations will begin on August 16, 2017 in Washington, D.C. Again, the President and the executive branch can negotiate and come to an agreement with trade partners, and by the letter of the law are meant to consult with Congress throughout, and present the new agreement to Congress for an up-or-down vote—no amendments to the agreement are allowed. Trade negotiations typically take years, although the Trump administration has said it hopes to finish NAFTA by the end of 2017 or early 2018.

The Trump administration has threatened to pull out of NAFTA if it cannot reach a satisfactory deal with Canada and Mexico. In that case, the U.S. would have to provide Canada and Mexico a six-month notification of its intention to withdraw. In the case of withdrawal, trade would not come to a screeching halt between the countries. Mexico would shift toward most-favored nation status accorded all WTO members with the U.S., while it is likely that the 1989 U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement, which also eliminated most tariffs between the two countries, would govern trade with Canada. Canada and Mexico could continue under the terms of NAFTA in trade between the two countries if they so choose.

Aside from the technical process for renegotiation, the lack of transparency and public input into trade policy has been one of the major targets of criticism of past trade deals, including the TPP. Past trade deals have been negotiated largely in private, with a selected delegation of mostly corporate advisors at the negotiating table. Members of Congress are allowed to read the draft negotiating texts only in a secure room with a guard posted. Neither electronic devices nor expert advisors may accompany the Member of Congress, as they try to understand hundreds of pages of rules and thousands of pages of tariff schedules. The Trump Administration gave citizens only a small window for public input on NAFTA and less than a month public comment period (but nevertheless received more than 50,000 comments). The Administration held only a single public hearing on the agreement over three days in Washington, D.C.

The Trump Administration has largely abandoned existing trade advisory committees set up through the U.S. Trade Representative and other government agencies by the Federal Advisory Committee Act. The White House instead has created new avenues of corporate involvement in government broadly—relying heavily on private interests to staff the administration from firms like Goldman Sachs and Exxon/Mobil. But the Trump Administration has also established an influential Business Council, chaired by the CEO of the agrochemical giant Dow Chemical, and including representatives from companies like Walmart, PepsiCo, and JP Morgan, among others.69

What are benchmarks for a new NAFTA?

Commerce Secretary William Ross has stated that the TPP should be the starting point for a NAFTA renegotiation.70 But the TPP was rejected largely because it continued a failed approach to trade which benefits corporate and financial interests.

A new approach to NAFTA for agriculture must start with a goal to rebuild farm and food systems that will support fair and sustainable rural economies and food supplies in all three countries. The following benchmarks for a new NAFTA have been identified by IATP, Food and Water Watch, the National Family Farm Coalition, the Rural Coalition, National Farmers Union and R-CALF71:

Improve the transparency of the trade talks

The input of rural communities and all affected sectors is crucial to an effective agreement. Public consultations must not be limited to a single hearing in Washington, D.C., as the Trump Administration has done. There should be regional consultations throughout the U.S., including rural parts of the country. The trade negotiations process itself must be made more transparent, as opposed to past trade negotiations, where much of the proposals and text have been kept secret. Future NAFTA documents should be made public to make it possible for meaningful debate on the agreement as it is being developed.

Eliminate the Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism

NAFTA was the first agreement to include ISDS. This highly controversial provision of NAFTA, which extends the rights of corporations to sue governments, has come under widespread criticism from civil society organizations in all three NAFTA countries. While there have been only a few cases involving agriculture this mechanism has been used repeatedly to threaten progress on environmental and water protections, and energy laws and regulations. For example, TransCanada recently sued the U.S. government over the cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline. The company dropped the case only after the Trump administration approved the pipeline (and backtracked on a campaign promise to require the use of U.S. steel). The Trump Administration’s notice of negotiating objectives to Congress in July outlined reforms for ISDS that very closely mirror minor reforms agreed to as part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, leaving in place the rights of corporations to sue governments.72

Restore Country of Origin Labels (COOL)

As part of the NAFTA renegotiations, the U.S. should request that Canada and Mexico not enforce the COOL ruling at the WTO. COOL supports the interest of consumers in knowing where their food comes from and gives additional value to farmers in the marketplace. COOL has been a source of friction between the three countries since the U.S. passed COOL in the 2002 Farm Bill. Mexico and Canada successfully challenged the original COOL, and then a revised more detailed COOL, at the World Trade Organization. The U.S. Congress withdrew COOL for meat in 2016 in response to the WTO rulings. Many U.S. farmer and rancher groups, like R-CALF, want COOL to be reinstated through a NAFTA renegotiation.73

Restore national and local sovereignty on farm policy

All nations should have the right to democratically establish domestic policies, including farm policies that ensure that farmers are paid fairly, and that protect farmers and consumers. Two critical policies essential for ensuring fair trade in agriculture focus on preventing dumping (when imports are unfairly priced below the cost of production) and protecting supply management systems. While the U.S. has existing tools to prevent agriculture dumping imports, it has not effectively applied them. For example, Florida tomato growers have been hit by an influx of Mexican tomatoes since NAFTA, and while several dumping investigations have taken place and temporary agreements reached74 major tensions remain. Mexico has applied antidumping duties on U.S. apples, and against U.S. exports of chicken thighs and legs.75 Additionally, anti-dumping rules don’t apply effectively to agricultural products that are seasonal and perishable, and where only parts of the country might be affected (like strawberries grown in Florida).

Supply management programs have been the steady target for elimination in the negotiation of free trade agreements. In the case of NAFTA, the U.S. dairy and poultry industry have long targeted Canada’s supply management system. Poultry companies like Tyson and Pilgrims Pride want some of the gains won under the TPP that weakened Canada’s poultry supply management system to transfer to NAFTA.76 Well run supply management programs help ensure prices are stable, and keep family farmers in business. The United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) in the U.S. is supporting Canada’s poultry and dairy supply management system, arguing that higher and more stable prices for farmers and growers is also better for workers.

Protect farmers’ rights to seeds

The biotech industry has been pushing for a TPP-like chapter on intellectual property in NAFTA, which would increase pressure on Mexico to change some of their intellectual property (IP) laws for seeds. The TPP required all countries to join the global seed breeders treaty, known as UPOV91, which prevents farmers and breeders from sharing seeds, while empowering global seed companies like Monsanto and Syngenta.80 Mexico is home to many ancient breeds of corn and tomatoes that are critical in adapting to climate change.81 Monsanto has long targeted Mexico’s intellectual property laws for seeds in order to sell genetically engineered corn in the country. A major civil society movement in Mexico has blocked the approval of Monsanto’s GE corn, most recently supported by a court ruling supporting the ban.82

Reject TPP proposals to speed adoption of new and unregulated agricultural technologies

The TPP was the first agreement to specifically identify rules for trade in GMOs. TPP provisions also apply to new, more powerful genetic engineering techniques, such as CRISPR. Importantly, the biotech rules were not within the food safety section of the agreement, but rather within the chapter related to tariffs (Market Access and National Treatment) with the goal of expediting the import of GMOs. The result was that human and environmental safety criteria involving GMOs and products derived from new technologies like plant synthetic biology would be considered in terms of how they affect trade. The U.S. Biotech Crops Trade Alliance has proposed that NAFTA require regulatory approvals of GE crops in one NAFTA party be accepted by the other parties, regardless of whether or not that approval was based on publicly available peer-reviewed data.83 The TPP’s biotechnology section would have prevented export rejection because of a low level presence (LLP) discovery of an unapproved GMO. By using the proposed TPP’s rapid response mechanism, the import of unapproved LLP GMO shipments would be expedited, reducing the time required for a thorough scientific risk assessment. The U.S. Biotech Crops Alliance is pushing to include the TPP language on low level presence, and to make that section legally binding, within NAFTA.84

Strengthen food safety protection

Food safety measures under trade agreements often make bold claims about protecting safety with “high standards”, but do not require countries to adequately resource their food safety system. A renegotiated NAFTA must oblige governments to provide adequate resources to implement the SPS chapter. A renegotiated NAFTA that adopts food safety provisions agreed to under the proposed TPP should not include provisions that grant food companies additional opportunities to challenge the rejection of shipments for food safety reasons. The U.S. Wheat Associates and National Association of Wheat Growers said they wanted to see the much weaker food safety rules negotiated in the TPP imported into a new NAFTA.85

Protect human and environmental safeguards

NAFTA created space for what is called “regulatory cooperation”, a process which seeks alignment of regulations, many related to food and agriculture, between signatory nations. But far from ensuring improvements in regulatory processes and systems, regulatory cooperation limits the ability of individual governments to innovate and improve regulations and regulatory systems under the pressure of meeting trade agreement provisions. The chemical industry, including agriculture chemical companies like Monsanto, Dow and DuPont, who favor less regulation of all kinds, are pushing hard for even higher levels of cooperation and streamlining based on risk, rather than a more rigorous hazard-based system.86 The next iteration of NAFTA’s Regulatory Cooperation could be the TPP chapter on Regulatory Coherence which created what amounts to an early warning system for the formation of regulations in all TPP countries, including state regulations. Regulations would then be periodically reviewed to determine whether they are still necessary. A new NAFTA should not undermine or weaken national-level regulations that protect public health and the environment.

Eliminate procurement provisions

NAFTA gave access to government procurement programs to companies from all participating countries. One of the exceptions to procurement program access was food-related programs. Communities across North America are working to transform local economic systems so that they are more sustainable and equitable. Many states are using public procurement to support these efforts. Farm to school programs incentivize purchases from local farmers. The Canadian government recently agreed to sweeping new trade rules governing procurement programs in the Canadian European Trade Agreement (CETA). Those changes should not be transferred to NAFTA. Public food programs at all levels should not be subjected to trade rules and procurement policy should be under the purview of state and local governments. A group of 11 Senators, including Senators Merkely and Baldwin, have called for the elimination of the Government Procurement chapter in NAFTA to protect local and Buy American provisions.87

Protect the rights of agricultural workers

While NAFTA does include a side agreement on labor, it has been unenforceable and ineffective in protecting workers. The immigration experience of NAFTA and increasingly draconian immigration policies have left the agribusiness sector deeply vulnerable to worker shortages, yet they remain largely unwilling to offer better working conditions. A new NAFTA must establish binding accords to protect farmworkers’ labor and human rights in all three countries. The AFL-CIO is calling for NAFTA to include collective bargaining rights and a strong minimum wage in all three countries—this could have major implications for food companies and particularly the meat processing industry which has almost no union membership in Mexico, and low union membership in U.S. poultry processing.88 The Trump administration’s NAFTA negotiating objectives do strive to move the labor agreements into the main text of the agreement, but otherwise repeat much of the language of past trade agreements that have been largely unenforceable.

Protect the right of governments to act on climate change

Climate change is already adversely affecting farmers and rural communities deeply connected to natural resource based economies in all three countries. Policies focused on addressing climate change are in place in all three countries – and more climate policies are in the process of being developed. While the Trump Administration has announced that it will withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, both Mexico and Canada remain part of the agreement. And many U.S. states and cities have announced their continued commitment to the Paris Agreement. Thus far, trade rules like those established in NAFTA have taken precedent over environmental and climate goals. Under a new NAFTA each country, state and local government should retain their sovereignty to enact and implement policies designed to reach their commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement.

Download the PDF of this paper.

Endnotes

1. North American Free Trade Agreement, Secretariat. Accessed: August 8, 2017. https://www.nafta-sec-alena.org/Home/Texts-of-the-Agreement/North-American-Free-Trade-Agreement.

2. U.S. Department of Agriculture. The North American Free Trade Agreement: Benefits for U.S. Agriculture. 1993.

3. U.S. International Trade Commission. Potential Impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement on Selected Industries. January 1, 1993. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub2596.pdf.

4. U.S. General Accounting Office. North American Free Trade Agreement: Assessment of Major Issues, Volume 1. September 1993. http://www.gao.gov/products/GGD-93-137.

5. Bradsher, Keith. “Last Call to Arms on the Trade Pact.” New York Times. August 23, 1993. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/23/business/last-call-to-arms-on-the-trade-pact.html?pagewanted=all.

6. Hufbauer, Gary, Jeffrey Schott. “North America Free Trade Agreement: Everybody Wins.” USA Today. September 1, 1993. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/North+American+Free+Trade+Agreement%3a+everybody+wins.-a013266589.

7. Suppan, Steve. Mexican Corn, NAFTA and Hunger. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. May 1996. https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/2017-07/Mexican%20Corn%2C%20NAFTA%20and%20Hunger.%20By%20Steve%20Suppan.%20May%201996_0.pdf.

8. M. Angeles Villareal and Ian F. Fergusson, The North American Free Trade Agreement, Congressional Research Service, February 22, 2017.

9. Stop Investor State Dispute Settlement. NAFTA. Accessed August 8, 2017. http://isds.bilaterals.org/?-isds-nafta-.

10. North American Free Trade Agreement, Secretariat. Accessed: August 8, 2017. https://www.nafta-sec-alena.org/Home/Texts-of-the-Agreement/North-American-Free-Trade-Agreement?mvid=1&secid=b6e715c1-ec07-4c96-b18e-d762b2ebe511.

11. Dawkins, Kristen, Steve Suppan. Sterile Seeds: the Impacts of IPRs and Trade on Biodiversity and Food Security. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. November 1996. https://www.iatp.org/documents/sterile-fieldsthe-impacts-of-iprs-and-trade-on-biodiversity-and-food-security-november-1-0.

12. Lilliston, Benjamin, Niel Ritchie. “Freedom to Fail: How U.S. Farm Policies have helped Agribusiness and Pushed Family Farmers to Extinction.” Multinational Monitor. July/August 2000. http://multinationalmonitor.org/mm2000/00july-aug/lilliston.html.

13. Ray, Daryll and Harwood Schaffer. The 1996 “Freedom to Farm” Farm Bill. Agriculture Policy Analysis Center. University of Tennessee. January 17, 2014. http://www.agpolicy.org/weekpdf/703.pdf.

14. Murphy, Sophia, Ben Lilliston, Mary Beth Lake. WTO Agreement on Agriculture: A Decade of Dumping. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. February 2005. https://www.iatp.org/documents/wto-agreement-agriculture-decade-dumping

15. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

16. Schaffer, Harwood, Daryll Ray. Trade Deals and U.S. Agriculture. Agriculture Policy Analysis Center. University of Tennessee. December 18, 2015. http://www.agpolicy.org/weekcol/802.html.

17. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

18. Clayton, Chris. “U.S. Corn Exports to Mexico Could be at Risk.” DTN. February 14, 2017. http://agfax.com/2017/02/14/u-s-corn-exports-to-mexico-could-be-at-risk-dtn/.

19. Johnson, Renee. The U.S. Trade Situation for Fruit and Vegetable Products. Congressional Research Service. December 1, 2016. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34468.pdf.

20. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

21. Mulvaney, Lydia, Megan Durisin. “Cattle Industry `Very Concerned’ About Trump’s Pledge to Renegotiate NAFTA. Bloomberg. February 6, 2017. http://www.westernfarmpress.com/livestock/cattle-industry-very-concerned-about-trumps-pledge-renegotiate-nafta.

22. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

23. Bullard, Bill. Post-hearing brief regarding U.S. Tran-Pacific Partnership Free Trade Agreement. R-CALF. March 16, 2010. http://www.r-calfusa.com/wp-content/uploads/trade/100316-Post_Hearing_Brief_TPP.pdf.

24. U.S. National Agricultural Statistics Service. Overview of United States Hog Industry. U.S. Department of Agriculture. October 29, 2015. http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/current/hogview/hogview-10-29-2015.pdf.

25. Wernau, Julie. “Trump’s Trade Policies Worry U.S. Cotton Farmers.” Wall Street Journal. February 12, 2017. https://www.wsj.com/articles/denim-dilemma-1486900803.

26. Hagstrom, Jerry. “Tax Idea Concerns Seed Trade.” DTN. January 31, 2017. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/news/article/2017/01/31/border-tax-disrupt-flow-seeds-u-s.

27. Burns, Christopher. “The number of mid-sized farms declined from 1992 to 2012, but their household finances remain strong.” Amber Waves. U.S. Department of Agriculture. December 2016. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/december/the-number-of-midsize-farms-declined-from-1992-to-2012-but-their-household-finances-remain-strong/.

28. Adjemian, Michael, B. Brorsen, Tina Saitone, Richard Sexton. “Thin Markets Raise Concerns But Many Are Capable of Paying Producers Fair Prices.” Amber Waves. U.S. Department of Agriculture. March 2016. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/march/thin-markets-raise-concerns-but-many-are-capable-of-paying-producers-fair-prices/.

29. Global Development and Environment Institute.” Feeding Factory Farms.” Tufts University. Accessed August 8, 2017. http://www.ase.tufts.edu/gdae/policy_research/BroilerGains.htm.

30. Mulvaney, Lydia. Jenn Skerritt. “Spoiling for Canada Fight, U.S. Dairies Push for Trump Deal.” Bloomberg. February 21, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-02-21/spoiling-for-fight-with-canada-u-s-dairies-push-for-trump-deal.

31. Wise, Timothy, Reforming NAFTA’s Agricultural Provisions. The Future of North American Trade Policy: Lessons from NAFTA, The Pardee Center, 2009.

32. Qualman, Darrin. Losing the farm(s): Census data on the number of farms in Canada. May 16, 2017. http://www.darrinqualman.com/number-farms-canada/.

33. O’brien, Patrick, John Kruse, Darlene Kruse. Gauging the Farm Sector’s Sensitivity to Immigration Reform via Changes in Labor Costs and Availability. American Farm Bureau Federation. February 2014. http://www.fb.org/issues/immigration-reform/agriculture-labor-reform/economic-impact-of-immigration.

34. Lehman, Karen. NAFTA, Mexican Agriculture Policy and U.S. Employment. Testimony before Congress. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. October 28, 1993. https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/451_2_98624.pdf

35. Weisbrot, Mark, Lara Merling, Vitor Mello, Stephan Lefebvre, Joseph Sammut. Did NAFTA Help Mexico? An Update After 23 Years. Center for Economic and Policy Research. March 2017. http://cepr.net/publications/reports/did-nafta-help-mexico-an-update-after-23-years.

36. Gallagher, Kevin. “What Will Trump Deliver on Trade?” American Prospect. May 10, 2017. http://prospect.org/article/what-will-trump-deliver-trade#.WRMisbUqaB4.twitter.

37. United Food & Commercial Workers International Union, CLC Minority Report to the Agricultural Trade Advisory Committee (ATAC) for Trade in Animals and Animal Products on the Negative Effects of Trans-Pacific Partnership on the Beef Industry. December 3, 2015.

38. Barrett, Rick. “Dairy Farms Fear Trump’s Immigration Policies.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. March 6, 2017. http://www.jsonline.com/story/money/business/2017/03/06/dairy-farms-fear-trumps-immigration-policies/98700808/.

39. Fox, Carly, Rebecca Fuentes, Fabiola Ortiz Valdez, Gretchen Purser, Kathleen Sexsmith. Milked: Immigrant Dairy Farmworkers in New York State. The Worker Justice Center of New York/The Workers Center of Central New York. 2017. https://milkedny.org/.

40. Jamrisko, Michelle. “I Need More Mexicans: A Kansas Farmers Message to Trump.” Bloomberg. June 20, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-20/-i-need-more-mexicans-a-kansas-farmer-s-message-to-trump.

41. Karst, Tom. “Industry Leaders Press Labor Issues to House Agriculture Committee.” The Packer. July 13, 2017. http://www.thepacker.com/news/industry-leaders-press-labor-issues-house-agriculture-committee.

42. Hagstrom, Jerry. “Immigration Raids Could Send Milk Prices Soaring.” DTN. April 17, 2017. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/perspectives/blogs/ag-policy-blog/blog-post/2017/04/17/immigration-raids-send-milk-prices&referrer=twitter

43. Adjemian, Michael, B. Brorsen, Tina Saitone, Richard Sexton. “Thin Markets Raise Concerns But Many Are Capable of Paying Producers Fair Prices.” Amber Waves. U.S. Department of Agriculture. March 2016. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44034/56926_eib148.pdf?v=42445.

44. Spieldoch, Alexandra. NAFTA: Fueling Market Concentration in Agriculture. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. March 2010. https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/451_2_107275.pdf.

45. Meyer, Gregory. “US Farmers Rattled by Trump’s Mexico Plans.” Financial Times. February 7, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/7016f032-ecf9-11e6-930f-061b01e23655.

46. Wise, Timothy and Betsy Rakocy. Hogging the Gains From Trade: The Real Winners From Trade and Agricultural Policies. Global Development and Environment Institute. Tufts University. January 2010. http://www.ase.tufts.edu/gdae/Pubs/rp/PB10-01HoggingGainsJan10.html.

47. Cargill. Patrick Binger Testifies at USTR NAFTA hearing. June 27, 2017. https://www.cargill.com/2017/cargills-patrick-binger-testifies-at-ustr-nafta-hearing.

48. JBS USA. Comment to the US Trade Representative regarding NAFTA Negotiating Objectives. June 14, 2017. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-2017-0006-0883.

49. US Meat Federation. Comment to the US Trade Representative regarding NAFTA Negotiating Objectives. June 18, 2017. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=USTR-2017-0006-1373.

50. Leonard, Rod. The USDA Plan for Deregulating and Privatizing Meat and Poultry Inspection: A Short History. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. December 13, 2013. https://www.iatp.org/documents/the-usda-plan-for-deregulating-and-privatizing-meat-and-poultry-inspection-a-short-history.

51. Food and Water Watch. USDA Audit Shows Canadian Slaughter Plants Not Equivalent. April 18, 2017. https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/news/usda-audit-shows-canadian-slaughter-plants-%E2%80%9Cnot-equivalent%E2%80%9D.

52. Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. NAFTA’s 20 Year Legacy and the Fate of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. February 2014. https://www.citizen.org/sites/default/files/nafta-at-20.pdf.

53. Government Accountability Office. Additional Actions Needed to Help FDA’s Foreign Offices Ensure Safety of Imported Food. February 27, 2015. http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-183.

54. Marler, Bill. “Why the US Imports Tainted Food That Can Kill You.” The Hill. September 24, 2017. http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/energy-environment/343444-why-the-us-imports-tainted-food-that-can-kill-you.

55. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

56. Wallace, Robert. The NAFTA Flu. Farming Pathogens. April 28, 2009. https://farmingpathogens.wordpress.com/2009/04/28/the-nafta-flu/.

57. Alumbaugh, JoAnne. “Mexico Pork Production Expanding Despite PEDv. Farm Journal’s Pork. October 20, 2014. http://www.porknetwork.com/pork-news/latest/Mexico-pork-production-expanding-despite-PEDv----279785622.html.

58. Glen, Barb. “PEDv Strikes Manitoba Hog Barns.” The Western Producer. June 2, 2017. http://www.producer.com/2017/06/pedv-strikes-manitoba-hog-barns/.

59. The Poultry Site. Avian Flu Outbreaks Discovered in Mexico. April 12, 2016. http://www.thepoultrysite.com/poultrynews/36856/avian-flu-outbreaks-discovered-in-mexico/.

60. CBC News. Bird Flu Confirmed on Farm in St. Catharines. July 8, 2016. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/news/avian-flu-1.3670625.

61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity. Accessed: August 8, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/effects/index.html.

62. Hansen-Kuhn, Karen, Sophia Murphy, David Wallinga. Exporting Obesity: How US Farm Policy and Trade Policy Transformed Mexico’s Food System. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. April 5, 2012. https://www.iatp.org/documents/exporting-obesity.

63. Barlow, Pepita, Martin McKee, Sanjay Basu, David Stuckler. “Impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement on high fructose corn syrup supply in Canada.” Canadian Medical Association Journal. July 4, 2017. http://www.cmaj.ca/content/189/26/E881.

64. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

65. Environmental Protection Agency. Sources of Greenhouse Gases. Accessed: August 8, 2017. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

66. USAID. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Mexico. May 2017. https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2017_USAID_GHG%20Emissions%20Factsheet_Mexico_0.pdf.

67. Environment and Climate Change Canada. National Inventory Report 1990-2015. Accessed: August 8, 2017. https://www.ec.gc.ca/ges-ghg/default.asp?lang=En&n=662F9C56-1#es-4.

68. Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. Summary of Objectives for the NAFTA Renegotiation. July 17, 2017. https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/Releases/NAFTAObjectives.pdf.

69. Feloni, Richard. “Here are the 17 Executives who Met with Trump for his First Business Advisory Council.” Business Insider. February 3, 2017. http://www.businessinsider.com/who-is-on-trump-business-advisory-council-2017-2/#kevin-warsh-distinguished-visiting-fellow-in-economics-at-the-hoover-institute-and-former-governor-of-the-federal-reserve-system-16.

70. Mayeda, Andrew, David Gura. “Ross Says TPP Could Form Starting Point for US on NAFTA.” Bloomberg. May 3, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-05-03/ross-says-tpp-could-form-starting-point-for-u-s-on-nafta-talks.

71. Food and Water Watch, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, National Family Farm Coalition, National Farmers Union, R-CALF, Rural Coalition. Principles of a New US Trade Policy for North America. Agriculture. January 27, 2017. https://www.iatp.org/blog/201705/principles-new-us-trade-policy-north-american-agriculture.

72. Fortnam, Brett. “NAFTA Draft Notice Includes Language Similar TPP Text on Investment, IPs, SOEs.” Inside US Trade. March 30, 2017. https://insidetrade.com/daily-news/nafta-draft-notice-includes-language-similar-tpp-text-investment-ip-soes.

73. R-CALF. Why and How Mandatory COOL Should be Reinstated Through the NAFTA Renegotiations. May 2, 2017. https://www.r-calfusa.com/mandatory-cool-reinstated-nafta-renegotiations/.

74. Villarreal, M. Angeles. U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues and Implications. Congressional Research Service. April 27, 2017. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL32934.pdf.

75. Zahniser, Steven, Sahar Angadjivand, Thomas Hertz, Lindsay Kuberka, and Alexandra Santos. NAFTA at 20: North America’s Free Trade Area and its Impact on Agriculture. Economic Research Service. U.S. Department of Agriculture. February 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=40486.

76. Nickel, Rod. US Farm Groups Pile on Canada as Trump Eyes Trade Fairness. Reuters. May 4, 2017. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trade-canada-agriculture-idUSKBN1802PH?il=0.

77. Inside US Trade. Milk Rises to the Top of Trump’s Trade Agenda. April 24, 2017. https://insidetrade.com/trade/milk-rises-top-trump-trade-agenda.

78. Holman, Chris. Milking Scapegoats. Wisconsin Farmers Union. April 19, 2017. http://www.wisconsinfarmersunion.com/single-post/2017/04/19/Milking-Scapegoats.

79. U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA Announces Plans to Purchase Surplus Cheese. Releases New Report Showing Trans-Pacific Partnership Would Create New Growth for Dairy Industry. October 11, 2016. https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2016/10/11/usda-announces-plans-purchase-surplus-cheese-releases-new-report.

80. Lilliston, Ben. TPP Fine Print: Biotech Seed Companies Win Again. Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. November 16, 2015. http://www.iatp.org/ blog/201511/tpp-fine-print-biotech-seed-companies-win-again.

81. Hares, Sophia. Mexico’s Native Crops Hold Key to Food Security, Ecologist. Reuters. June 13, 2017. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mexico-environment-food-biodiversity-idUSKBN1942KY.

82. Garcia, David Alire. “Monsanto Sees Prolonged Delay on GMO Corn Permits in Mexico.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. January 30, 2017. http://www.stltoday.com/business/local/monsanto-sees-prolonged-delay-on-gmo-corn-permits-in-mexico/article_eb858f3e-7a1c-50da-9cf5-98eaa3419694.html.

83. Fortnam, Brett. “Ag Groups Seeks Biotech Rules in NAFTA that go Beyond TPP Provisions.” Inside US Trade. June 16, 2017. https://insidetrade.com/daily-news/ag-groups-seek-biotech-rules-nafta-go-beyond-tpp-provisions.

84. Ibid.

85. Fortnam, Brett. “Industry, Labor Groups Begin to Lay Out Priorities for NAFTA Renegotiation.” Inside US Trade. May 19, 2017. https://insidetrade.com/daily-news/industry-labor-groups-begin-lay-out-priorities-nafta-renegotiation.

86. American Chemistry Council. Joint Statement by ACC, CIAC and ANIQ on NAFTA. May 1, 2017. https://www.americanchemistry.com/Media/PressReleasesTranscripts/ACC-news-releases/Joint-Statement-by-ACC-CIAC-and-ANIQ-on-NAFTA.html.

87. Kitroeff, Natalie. “What’s on the Table in a NAFTA Negotiation.” Los Angeles Times. April 28, 2017. http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-nafta-negotiation-20170427-htmlstory.html.

88. AFL-CIO. NAFTA Negotiation Recommendations. June 12, 2017. https://aflcio.org/sites/default/files/2017-06/NAFTA%20Negotiating%20Recommendations%20from%20AFL-CIO%20%28Witness%3DTLee%29%20Jun2017%20%28PDF%29_0.pdf.