Rural America makes up only 16 percent of the U.S. population, but 90 percent of the land.1 Most of the resources we depend upon—food, water, energy, fiber and minerals—are either derived from or heavily impacted by rural land use, and stewarded by rural community members. These resources are imperative to the success and basic survival of our country, yet there is no comprehensive rural policy in the United States to plan, develop or sustainably manage these resources. Moreover, the current piecemeal approach to rural policy that we have today, found within the U.S. Farm Bill, is both chronically underfunded and, in the most recent negotiations, threatened with almost complete elimination.

This is the exact reverse of what is required. In our current discussions about what we need in a new U.S. Farm Bill, rural policy should be a primary area of focus. As we look to our rural communities to produce more—more food, more energy, more jobs—and to do it better, in cleaner, more efficient, more renewable ways, it is essential that we provide balanced support for these increasing and expanding demands. And this needs to be done in a way that not only ensures better stewardship but keeps more of the ownership and benefits in these rural areas rather than simply acting as a resource to be extracted by multinational corporations.

But resources alone are not enough; to truly address the current and future rural challenges, we must also create a unifying policy framework that acknowledges and optimizes the connections among natural resource and land-use management, farming, rural community development, and food and energy systems.

The Farm Bill and rural communities

What passes for rural policy today is embedded within the increasingly misnamed U.S. Farm Bill. Currently, this behemoth piece of legislation is the main vehicle for influencing how rural land is used and managed, yet it is anything but a comprehensive or cohesive policy. Instead, it is a collection of policies and programs that have been assembled over time to address different aspects of farm, food, forestry and rural concerns.

Agriculture continues to be prominent in most rural economies, but consolidation within the agricultural sector and the loss of family farmers over the last 50 years has significantly reduced the direct correlation between farm and rural community policy.2 Today, almost 90 percent of farm household income is derived off the farm.3 Yet policy, and certainly funding, have not kept up with this reality.

Farm Bill Conservation Programs

The Farm Bill includes many different programs aimed at conserving our nation’s natural resources. Priority areas within these programs are preventing soil erosion, reducing pollution to surface and ground water, and ensuring appropriate and sufficient habitat for wildlife. Overall there are a total of 15 program areas under the Conservation Title. In general, these are divided into the following areas:

Land retirement/set-aside programs These are programs that are intended to protect our most sensitive landscapes and natural resources. The biggest of these is the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), with almost 30 million acres currently enrolled across the country.4 Other similar programs include the Wetlands Reserve Program, the Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program, and the Healthy Forests Reserve Program.

Research and Coordination Finally, recognizing that research, planning and coordination are critical for ensuring appropriate conservation strategies, there are several funding and coordination programs in the Conservation Title, including Conservation Innovation Grants, the Cooperative Conservation Partnership Initiative, and the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Initiative.

Working lands programs These programs target conservation on productive lands. This is done through both financial and technical assistance to farmers and landowners, to educate them on conservation concerns and to help them understand and develop plans to reduce soil erosion, water pollution, and pesticide run-off and leaching. Included under this area are the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, the Agricultural Management Assistance Program, the Grassland Reserve Program, and the Farm and Ranch Lands Protection Program. In 2002 a new program was introduced, which is today known as Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP).5 CSP focuses on the whole farm, rather than individual areas of concern, and emphasizes outcome-based environmental performance, rather than prescriptive practices. Since its inception, there have been over 40 million acres enrolled in CSP.6

Programs focused specifically on rural interests beyond production agriculture receive, in the most generous of apportioning, ten percent of the total Farm Bill budget, and that percentage is only reached if one includes the Conservation Title programs, which make up approximately nine percent of the total Farm Bill expenditures. These programs, including both “land retirement” and “working lands” components (see box), are aimed primarily at land owners to mitigate the negative environmental impacts of their farming and forestry practices and to protect and enhance our natural resources.

Generally associated with agriculture, the programs in the Conservation Title are also at their base community programs. Created in the aftermath of the Dust Bowl, the conservation programs are intended to address such concerns as soil erosion, water and air quality, flooding risks and wildlife habitat. Though focused on individual landowners and their resource management, the success or failure of conservation efforts can make a very big difference in rural community environmental health, recreation opportunities and quality of life.

If one excludes the conservation programs, Rural Development receives less than one percent of the entire Farm Bill budget.7 This small amount of funding, dispersed among different Farm Bill titles, is intended to address some of the specific rural concerns around housing, infrastructure, financing, business development, etc. However, similar to the conservation programs, the profusion of programs combined with chronic, insufficient funding has resulted in a piece-meal and shallow programmatic approach that largely fails to meet USDA’s stated goals of improving the economy and quality of life in rural America.8

Rural development and energy opportunities

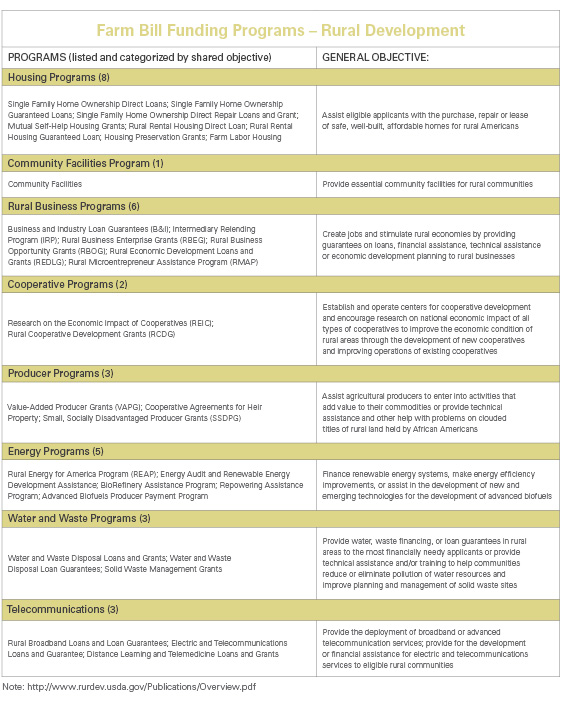

The Rural Development Title was introduced in the 1970 Farm Bill. Currently, its programs are focused primarily around helping rural communities with infrastructure planning and financing, economic and small business development, and community empowerment.9 Rural development programs help communities with such necessities as water and sewer systems, low-income housing, health clinics, and emergency electrical and telephone service. In general, these programs are restricted to official “rural” communities, which are typically defined by the USDA as “open country or settlements of 2,500 or less,” although there is discretion in this definition as communities of up to 50,000 people are eligible for many programs.10

Programs within the Rural Development Title fund business endeavors that are intended to meet the needs of a changing rural America. For example, in Adrian, Minnesota, a Rural Business Enterprise Grant helped the community overcome the potential loss of its pharmacy by building a telepharmacy, which connected a satellite pharmacy in Adrian to a central support location in the larger, nearby town of Worthington to expand its benefits. The telepharmacy option ensures that rural areas of Minnesota can still have a hometown pharmacy, a critical need in an increasingly less mobile community comprised of 35 to 40 percent seniors. Working with these smaller, more geographically dispersed towns offers opportunities for planners and community leaders to think about community-based development and infrastructure needs in a different, more scale-appropriate way.

Many of the programs within the Rural Development Title are in great need of the services provided by planners, but they are often hard to recognize. For example, several of these specific grant programs that support renewable energy systems, like the Value Added Producer Grant, may be used for working capital or planning purposes, which can include feasibility studies, marketing plans, business plans, and legal evaluations. For some programs, planning is even required; any renewable energy project financed through Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) in excess of $200,000 total project cost requires a feasibility study.

Energy was introduced as an official title of the farm bill in 2002 and expanded significantly in 2008. Developed immediately after the passage of the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA), many of the programs in the 2008 Farm Bill Energy Title were intended to help meet the renewable fuels goals laid out in EISA. Several of these are focused on the refineries themselves, providing support for retrofits and efficiency improvements, but there was also a new program introduced, the Biomass Crop Assistance Program (BCAP), which was aimed at helping farmers grow the crops expected to be used as feedstocks for the next generation of biofuels.

Rural development, conservation and energy: on the cutting block

The programs focused on rural development, energy production and conservation are critical for our communities, especially as we move into a more carbon-constrained future that requires a different approach to energy, community planning and infrastructure. This is especially so today, as high crop and land prices are incentivizing ever-higher levels of production, making conservation programs less competitive at the very same time governments are financially strapped. Yet the resources dedicated to these areas have always been less than requested, and certainly far below levels needed to meet all of the qualifying applications for support. Unfortunately, if early signs from the new round of Farm Bill negotiations are accurate, there will be even less money for these essential rural programs.

In information leaked from the “Super Committee” Farm Bill negotiations, almost all of the Rural Development programs were proposed for elimination, and only one to three of the energy programs were expected to survive with drastically reduced budgets. Programs that focus on rural housing, water treatment, business development, infrastructure, etc., with budgets in the millions of dollars, are being sacrificed to help fill a gaping multi-billion dollar federal budget deficit. Conservation programs are expected to fare somewhat better but also likely face significant cuts in budgets and programs.

The Biomass Crop Assistance Program (BCAP)

The Biomass Crop Assistance Program (BCAP) was created in the 2008 Farm Bill to help address a “chicken and egg” problem associated with the expected new energy economy: farmers are hesitant to grow a new crop without an established market, yet energy producers are unwilling to invest in a technology or facility without a reliable and known feedstock supply. BCAP seeks to solve this dilemma by providing financial assistance to farmers to plant and manage new, non-commodity crops—such as perennial grasses and fast growing trees—intended to be the low-carbon feedstocks for next generation bio-energy and biomaterials production.

The first BCAP project area approved, nearly three years after the bill was enacted, was Show Me Energy Cooperative, a Missouri-based, farmer-owned cooperative which produces pellets from a variety of plants and plant residues for energy purposes. They were awarded $15 million for farmers in 39 counties in Missouri and Kansas to plant and care for fields of mixed native prairie plants, including switchgrass. BCAP projects, like Show Me Energy, have powerful capacities to provide ecological services and conserve resources, while also producing marketable agricultural commodities using a broad palette of both perennial and annual plant species.

While there are undoubtedly opportunities to reduce the profusion of programs and increase efficiency of program delivery, this level of funding cuts could be traumatic for rural America. If we are looking to our rural areas for increased and expanded production—not only of food, but of renewable energy and materials, as well as the people needed to manage and produce these necessities—this downward trajectory for rural policy needs to change. To ensure not only the successful stewardship of these critical natural resources, but also that rural communities themselves are sharing in the benefits, we need to take a much more comprehensive, adaptive and supportive approach to our rural development and land-use policy.

Farm Bill debates only arise every five years, and the time to influence the rural economy and development is now. In the current negotiations and fiscal situation, the focus should be on retaining the critical functions and funding—if not necessarily all the programs—focused on conservation, rural energy efficiency and production, and rural development. But looking beyond 2012, we need to think much bigger. Rather than taking the backseat, rural policy needs to be up-front, transformed and expanded to create a more comprehensive, long-term policy that enables rural America to meet the challenges of the future.

Endnotes

1 USDA Economic Research Service (ERS): http://www.ers.usda.gov/.

2 USDA ERS: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib24/eib24b.pdf.

3 http://www.nationalaglawcenter.org/assets/crs/RL31837.pdf.

4 http://www.fsa.usda.gov/Internet/FSA_File/jan2012crpstat.pdf.

5 It was originally called the “Conservation Security Program.”

6 Calculated based on information reported by the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, www.sustainableagriculture.net.

7 There’s actually quite a bit in here, including the entire U.S. Forest Service, marketing and trade, research and education, and many other smaller programs. For more specific info, see: http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/usdahome?navid=PROGRAM_AND_SERVICE.

8 http://www.rurdev.usda.gov/AboutRD.html.

9 http://www.rurdev.usda.gov/Home.html.

10 http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/rurality/NewDefinitions/.