Introduction: If we can’t agree about climate finance, let’s start a new carbon market!

Climate finance for developing countries — who contributes and how much; what type, either in the form of grants or loans that would add to developing country debt burdens; and who benefits — is the headline issue of the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Nov. 11-22 in Baku, Azerbaijan. The New Collective Quantified Goal for Climate Finance (NCQG) would replace the 2009 pledge to “mobilize” $100 billion annually in climate finance by 2020. A report commissioned by COP26 and COP27 hosts estimated that at least $1 trillion in climate finance would be needed annually by 2030. However, a NCQG co-chairs report on the climate finance negotiations noted with diplomatic understatement, “Concerns were raised by some participants about the lack of clarity regarding the quantum of the NCQG and the amount that developed countries are willing to provide or mobilize under the NCQG” (p. 14, paragraph 61). If COP29 Parties (governments) cannot agree on the terms of the NCQG, as seems likely, other items on the COP29 agenda may receive more attention.

As the NCQG talks falter, debate about a controversial form of climate finance is also on the COP29 delegates to do list: agree on how to start trading greenhouse gas emissions credits under the terms of the UNFCCC Paris Agreement Article 6.4. The implementation of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism faces some of the same challenges as the emissions reduction projects and credits of private sector organizations. How can the private sector buyer of a credit from a Party to the Paris Agreement be assured that the credit claiming to reduce one metric ton of CO₂ equivalent emissions will still represent that quantity of emissions reduced at the end of the crediting period? How can the buyer be assured that the land and human rights of those residing in the emissions reduction project area have not been violated in a project’s establishment and maintenance? But the Article 6.4 implementation negotiations have an additional challenge that private standard setters do not face: differences among the Parties, e.g., concerning carbon accounting methodologies, that have stymied the implementation agreement at COP28 and earlier COPs.

However, on Oct. 9, the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body (A6.4 SB), a group of 12 diplomats and 12 alternates serving in their “personal capacity” rather than as representatives of their governments, presented the COP government delegates with a done deal that may pre-empt debate. The done deal is a breakthrough for those seeking to fast-track Article 6.4’s implementation terms and align them with private carbon crediting standards. COP29 government delegates are unlikely to refuse the deal by consensus in Baku, particularly if there is no agreement on climate finance.

Geo-politically, COP29 requires a deliverable to demonstrate the viability of the Paris Agreement: the A6.4 done deal may be it. Furthermore, as corporations pull back from buying credits that claim to offset their emissions, particularly renewable energy offsets, some carbon market proponents see an Article 6.4 deal as a strong signal of government support for struggling voluntary carbon markets subject to no government regulation. According to Carbon Pulse, investors are already speculating financially on the carbon credit types expected to be issued for sale under Article 6.4 terms.

This article analyzes three A6.4 SB documents, two of them now in force and necessary to legally jump start the issuance and sale of credits, mostly from developing country Parties to the Paris Agreement to non-Parties, mostly corporations headquartered in North America and Europe. One policy expert quoted by the Financial Times said the A6.4 SB documents made the Paris Agreement carbon trading “mechanism” “basically operational.” Our analysis points out how the A6.4 SB has agreed on high level requirements, principles and guidance to make the mechanism operational in principle, but the practical operation of the mechanism still must overcome several hurdles.

To achieve agreement, A6.4 SB members postponed addressing such contentious issue as the criteria for determining an “avoidable” emissions reversal. An unavoidable emissions reversal is, for example, when a forest fire wipes out part or all of emissions reductions claimed in a validated emissions reduction project. Apparently unable to agree on what constitutes an avoidable emissions reversal, the A6.4 SB removals standard simply states, “Mechanism methodologies shall, in addition to the above, follow further guidance developed by the Supervisory Body on avoidable and unavoidable reversals” (page 11, paragraph 63). Like the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, the A6.4 SB optimistically envisions a process of “continuous improvement” to the Paris Mechanism rules that will resolve any future implementation problems.

The Article 6.4 Supervisory Body circumvents a diplomatic impasse

The A6.4 SB recommended text was not adopted at COP28, in part because the text did not provide robust environmental and social safeguards against credit-seeking projects that misreported emissions reductions, and/or violated land rights and human rights of the local communities and Indigenous Peoples residing in the project areas. However, the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA) did not provide much guidance about how the A6.4 SB should revise the text. The emissions removal recommendation text received an array of criticisms. (See the Third World Network’s reporting for a blow-by-blow accounting of the Article 6.4 debate [pages 82-85].)

For COP29, the A6.4 SB decided to take matters into their own hands by revising and shortening three Article 6.4 texts to elide sources of disagreement and convert the texts from recommendations for the CMA’s consideration to standards that the A6.4 SB could approve under its own authority. The A6.4 SB presented the justification for its solution to the CMA impasse in its Oct. 10 newsletter that announced the adoption of the removals and methodologies standards:

“The Supervisory Body took a different approach to its recommendations to the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA). To ensure the mechanism can remain agile and adapt to ever evolving developments in addressing climate change, they adopted the elements requested by the CMA as ‘Supervisory Body standards’ and requested the CMA to endorse this approach and provide any additional guidance. This allows the Supervisory Body to review and further improve these standards whenever necessary.”

In a nutshell, the A6.4 SB has emulated the “continuous improvement” approach of the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) to carbon credit standards and assessment development. It is likely that the CMA will adopt the standards, notwithstanding criticisms and objectives from some delegations, if only because private crediting organizations, such as Verra, are already beginning to issue some credits for sale with the ICVCM “Core Carbon Principle” label. To the extent that A6.4 emissions reduction credits compete for buyers with voluntary carbon credits, the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism is at a competitive disadvantage. ICVCM credit types with the CCP label are already on the market. Credits issued for sale under the rules of the Paris Mechanism might not be on the market before 2026, if then.

In June, the ICVCM announced the first 27 carbon credit program types eligible for the ICVCM’s “high integrity” carbon credit label. The announcement cited a joint statement by Michael Bloomberg, UN Special Envoy on Climate Ambition and Solutions, Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance, and Mary Schapiro, Head of the Secretariat for the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: “Policymakers should adopt common supply, demand, market, and social integrity standards. This work should leverage the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) supply-side standards and labelling, which several countries are already considering backing.” It appears that A6.4 SB negotiators are heeding that advice.

Overview of three Article 6.4 documents required to start selling Article 6.4 emission reduction credits

The A6.4 members and alternates, assisted by the UNFCCC Secretariat and expert groups, have produced a large body of regulations for governance, accreditation, activity cycles and methodologies, as well as standards, procedures and tools. These documents contain mandatory and voluntary provisions to be used by any entity that wishes to participate in the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism.

The documents analyzed briefly here concern three issues: 1) the types of emissions removals projects and corresponding credits to be issued on the Mechanism registry; 2) the methodologies to be used to determine credible baselines from which emissions reductions are calculated and to determine if the projects provide evidence to demonstrate that they result in additional emissions reductions that wouldn’t have occurred without the projects; 3) a Sustainable Development Tool comprising 11 principles, corresponding evaluation criteria and a risk assessment survey to enable emissions reduction project developers to document whether their projects pose risks and/or offer UN Sustainable Development Goal benefits as part of the validation process for their projects.

The removals standard for COP29

The removals recommendation presented to the delegates at COP28 sought to elide controversies over specific removal technologies, such as Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). The recommendation characterized any mention of specific “activity types or categories” as “purely illustrative” and without legal effect in the A6.4 SB decisions (paragraph 6b, page 7, Version 03.0). The A6.4 SB amended that provision in a subsequent draft by adding “unless explicitly indicated as such” (page 3). This amendment is necessary because an Article 6.4 registry of emissions reduction credits for sale and “retired” (cancelled and not reusable to prevent double counting of the credits) can only operate if the credit type is explicitly specified for the credit buyer. As IATP noted in our analysis of that COP28 recommendation, “[s]emantic removal of controversy does not, however, remove substantive and implementation challenges concerning removal project types.” An October article in Nature warned that promoters of Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies were over-confident that climate catastrophe could be averted by removing greenhouse gases after the 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius threshold had been crossed. Thus far, negotiators and CDR technology promoters, including fossil fuel companies, have not heeded such warnings.

The removal standard presented as a done deal to COP29 delegates refers to what earlier drafts of the removals recommendation had described as “engineering-based solutions” for emissions reductions. The new definition of “removals” references the definition of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (paragraph 8a, page 4) but is amended to accommodate emissions “destruction” in Bioenergy and CCS (BECCS) and other engineering-based solutions: ”For this document, (a) Removals are the outcomes of processes by which greenhouse gases are removed from the atmosphere as a result of deliberate human activities and are either destroyed or durably stored through anthropogenic activities” (page 4, paragraph 9). (As outlined below, the methodologies standard instructs whoever develops the methodologies to support engineering technologies that are not technologically proven or commercially viable.)

Has the A6.4 SB assigned to itself the quasi-legislative role of the CMA? The A6.4 SB, a body of individuals acting in their “personal capacity” and not as representatives of their governments, is described as the regulator of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism, The removals standard allows the A6.4 SB to intervene as it sees appropriate at all stages of the development of credits derived from emissions removal projects.

For example, according to the A6.4 SB’s “Accreditation standard”, a Designated Operational Entity (DOE) approved by the A6.4 SB validates the design documentation of emissions removal projects and another DOE verifies the emissions reductions claimed by project developers. The DOE should monitor the implementation of the project, including when extreme weather events, technological failures or bureaucratic shortcomings result in a reversal of emissions reductions claimed by the project developer. Per the removals standard, the A6.4 SB may intervene to review a project developer’s monitoring plan and assessment of the emissions reversal risk: “The designated operational entity (DOE) or the Supervisory Body identifies the need to revise the monitoring plan based on any concerns identified with the monitoring plan and the risk assessment plan” (page 5, paragraph 17a).

Given the likelihood of emissions reversals, e.g. as the result of wildfires or floods, it is not surprising that about half of the 12-page removals standard concerns requirements for monitoring reports and risk assessment of emissions reversals. However, it is far from clear how the A6.4 SB, at this point a negotiating body, can be authorized and resourced, even with the help of an expanded UNFCCC Secretariat, to become a hands-on regulator overseeing the DOEs. Among DOE duties is to oversee the emissions reduction project developers (“activity participants”) who originate and implement those projects, including the meetings with local communities and Indigenous People who reside in the project boundaries. Activity participants are required to share their project risk assessments and project monitoring plans at these meetings before the DOEs are validated and during the life cycle of each project.

Absent emissions reversals, emissions removal projects should result in emissions reductions to slow the momentum towards climate catastrophe. In the removals standard requirements, “Where an activity involving removals also results in emission reductions, the accounting of removals and emission reductions shall be separated in the monitoring report in accordance with the methodology applicable to the activity” (page 8, paragraph 34). This requirement would enable a separate accounting of emissions removals verified by the DOE and an accounting for emissions reductions. Emissions reductions are entered into the monitoring report after the activity participant has “fully remediated” in accounting terms the emissions reversals with emission reduction credits drawn from the Reversal Risk Buffer Pool Account to be established by the A6.4 SB and administered by the Article 6.4 registry mechanism (paragraph 53, page 10).

One factor that complicates this accounting process is that the methodologies have yet to be agreed on and the activity types have yet to be specified. The methodologies standard, as explained below, does not stipulate methodologies, only high-level requirements for whomever develops specific methodologies for certain activity types, such as CCS projects. The removals standard’s near elision of project types from the standard, compared to the COP28 recommendation text, risks the conflation of nature-based emissions removals projects for temporary storage of greenhouse gases with engineering-based projects intended to result in durable storage. Carbon Market Watch has remarked about the risk of assuming in carbon accounting that temporary biogenic storage will “offset” fossil fuel emissions and that technical solutions will store greenhouse gases for a long duration:

The role of carbon dioxide removals in our climate action hierarchy is still poorly understood or willfully distorted. Temporary ‘removals’, such as when carbon is sequestered and stored by natural ecosystems, do not and cannot balance out emissions. Meanwhile, technical solutions, such as Direct Air Capture and Storage, that remove carbon dioxide more permanently, and thus have a higher potential to effectively supplement climate mitigation, remain in prolonged infancy, are unproven at scale and could involve more lifecycle emissions than they remove.

The A6.4 SB removals standard has suppressed controversies that would arise in a CMA debate about the technological and economic viability of different project types to reduce emissions sharply in the near term to achieve the 1.5 degrees Celsius goal of the Paris Agreement. For Parties who hoped to build a carbon credit project industry, how many project developers will be able to meet this requirement? “Activity participants should obtain and maintain sufficient coverage under an insurance policy or comparable guarantee products to cover the risk that avoidable reversals occur” (p. 11, paragraph 59). Without an agreement among Parties on what constitutes “avoidable risk,” what kind of insurance company writes a policy for “avoidable risk”? If emissions reversal events become ever more frequent and severe, how they could have been avoided may be difficult to determine. Does insurance for “avoidable risk” become unavailable or unaffordable for all but the largest legacy project developers?

The removals standard may buy some time for Article 6.4 expert groups to give scientific and economic appraisals of the removal project types and their potential to reduce emissions. The A6.4 SB has promised to provide guidance to the Parties about what constitutes avoidable and unavoidable emissions reversals (page 11, paragraph 63) to resolve contentious issues, such as whether avoidable reversals can be fully remediated with emission reduction credits from the Reversal Risk Buffer Pool Account. The longer the A6.4 SB postpones or pre-empts Party debate about contentious issues in the Article 6.4 implementation rules, the more time will pass before 6.4 emission reduction credits are issued for sale to private sector buyers.

The methodologies standard

Perhaps the first thing to know about the methodologies standard is that for the most part it does not contain methodologies, e.g. on how to set the baseline from which emissions reductions are estimated. Rather it contains requirements and guidance for how methodologies are to be developed for unspecified types of removal projects. For example,

Mechanism methodologies should facilitate the deployment of technologies or measures that are not widely used or available in specific locations, to facilitate knowledge transfer and encourage deployment of technologies or measures that reduce the cost of decarbonization and unlock investment in low-carbon solutions (page 4, paragraph 19).

This paragraph is from the “Methodology Principles” that comprise about half of the 14-page document. It is possible for an expert group to develop a calculation for determining a baseline for a current emissions reduction activity type. However, it is not clear how climate science-based methodologies (page 4, paragraph 9) can assist in knowledge transfer, e.g. concerning expensive CCS systems from companies in wealthy countries to private or public entities in poor ones.

The Paris Agreement does not have a glossary of terms, so private organizations have written glossaries that serve our explanatory purposes here. For example, Gold Standard, an emissions crediting program, has defined “methodology” as

The approach – or method - that a given activity must take to calculate the emission reductions or removals achieved as a result of its activity, including how it must take into account factors such as leakage. Each methodology is specific to a type of activity, such as renewable energy production, the distribution of lower-emission and cleaner cookstoves or the afforestation of areas of land. . . (page 6)

This definition is applicable to those principles that guide the development of methodologies by A6.4 expert groups vs. those principles whose implementation is the purview of regulators in the Parties hosting the emissions reduction projects.

Among those principles from which methodologies should be developed by expert groups are those concerning emissions baselines, avoidance of “leakage” in project design and implementation, and methodologies to demonstrate that projects provide emissions reductions in addition to whatever reductions are required by governments. For example, “Mechanism methodologies shall contain credible methods for estimating emission reductions or removals to ensure that the results of Article 6.4 activities represent actual tonnes of GHG emissions reduced or removed. Such estimations shall be based on up-to-date scientific information and reliable data” (page 5, paragraph 22). This is a principle for developing methodologies in the conventional sense of the term. Such methodologies, properly implemented, ensure that emissions reduced or removed are not erroneous or misrepresented by project developers to DOEs who must verify the accuracy of the emissions claimed for the issuing of credits.

Other principles for developing methodologies probably could be implemented only after agreements among the Parties. For example, one principle requires that “Mechanism methodologies shall contain provisions for contributing to the equitable sharing of mitigation benefits between participating Parties, including the application of conditions specified by the Designated National Authorities (DNAs) of the host Party” (page 6, paragraph 31). The role of the DNAs is very seldom mentioned in the removals and methodologies standards, though that role may be defined in other documents not reviewed here. However, unlike a methodology developed according to the best available science, a methodology for the “equitable sharing of mitigation benefits” is applied according to conditions, which may or may not be science based, specified by the DNAs of the Parties hosting the emission removals or reduction projects. Those conditions may vary from Party to Party. If “equitable sharing of mitigation benefits” points towards a fair share of financial proceeds from the sale of emissions reduction credits, that can be the subject of a methodology negotiation. The phrase could be understood to mean that a Party selling credits might both benefit from the sale financially, but also use the credits as a Nationally Determined Contribution to emissions mitigation. However, such an interpretation would violate the Paris Agreement provision to “ensure the avoidance of double counting, in accordance with guidance adopted by the” CMA (page 5, paragraph 13). If an agreement on a methodology to sharing mitigation benefits, financial or otherwise, is a prerequisite to begin operating the A6.4 registry, it may be some time before the first A6.4 emissions reduction credit is registered.

The Sustainable Development Tool (SD Tool)

The Article 6.4 Sustainable Development Tool (SD Tool) comprises principles, criteria and survey questions to help emissions reduction project developers to conduct a “do no harm” risk assessment concerning social and environmental safeguards. A separate set of questions helps project developers self-assess whether their projects support and/or pose any risks to the realization of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

The use of the SD Tool by project developers (“activity participants”) is mandatory for those who wish to issue credits under the Paris Mechanism for sale to non-Parties. The “activity participants are required to document in the activity form [project design document (PDD)] that their proposed activities do not cause any environmental and/or social harm by completing A6.4 Environmental and Social safeguards risk assessment form and the Environmental and Social Management Monitoring Plan for addressing environmental and/or social risks identified in A6.4 Environmental and Social safeguards risk assessment form” (page 7, paragraph 11). Designated Operational Entities (DOEs), accredited by the A6.4 SB, review the risk assessment form to determine whether the responses to risk assessment questions are well substantiated and to approve or require revisions to the risk assessment. The DOEs must likewise review and approve the project developers’ Monitoring Plans as part of the project validation process.

Furthermore, the use of the SD Tool is mandatory to transfer credits from the UNFCCC’s Kyoto Protocol Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) to the Paris Mechanism credit registry (page 4, paragraph 6). The Kyoto Protocol ceased to operate in 2020, so no new CDM projects have been approved or CDM credits issued. For the approximately 2.4 billion Certified Emissions Reduction (CERs) credits on the CDM registry to transfer to the Paris Mechanism, once it is operational, the CDM’s 7,839 registered projects in developing countries must be retroactively validated and their CERs retroactively verified by A6.4 SB approved DOEs. This credit transfer may be diplomatically necessary to secure developing country support for the standards to be used to operate the Paris Mechanism’s registry.

However, CDM credits are often of low quality because of subjective and frequently revised standards used to validate projects and certify emissions reductions. Climate economist and lawyer Danny Cullenward explained a major cause of the low quality of CDM credits:

The main problem is that many CDM projects earned carbon credits for things that were going to happen anyway. This outcome violates a standard known as additionality, a common requirement across carbon markets (including the CDM).

Cullenward referenced studies showing that only a low percentage of CDM project developers were able to provide quantitative evidence of additionality. He pointed to a structural problem with CDM standards: “In the CDM’s bottom-up process, methodologies are developed by private parties for review and approval by rotating panels of experts. Projects that game these rules will be detected only if regulators know as much or more than project developers and want to act.” Because the A6.4 SB is the Paris Mechanism’s regulator and the SD Tool’s implementation is partly a bottoms-up process, the pressure on DOEs to retroactively validate the CDM registered projects, whether or not they comply with A6.4 SB requirements, will be significant.

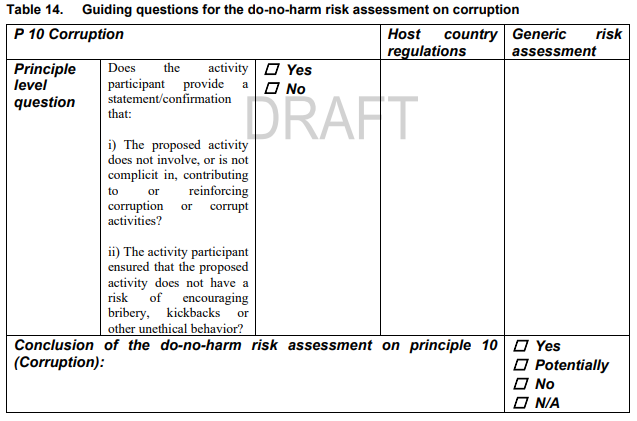

To counter that pressure both regarding CDM credits and Paris Mechanism credits, the A6.4 could have proposed measures to prevent corruption, one of the 11 principles to be implemented in the environmental and social safeguards. In a Sept. 30 letter to the A6.4 SB, IATP praised improvements made to the prior version of the SD Tool to provide a clearer and more comprehensive legal framework for the risk assessment of environmental and social safeguards in the project validation process reviewed and approved by the DOEs. But we argued that to implement the safeguard to prevent and avoid corruption the role of the relevant Designated National Authority (DNA), i.e., as designated by the Parties, would have to be specified. DOEs accredited by the A6.4 SB to validate project designs and verify emissions reductions resulting from those projects do not have the authority or resources to investigate potential cases of corruption and prosecute those involved if warranted by the evidence. Instead, the SD Tool provides just this self-assessment question about corruption for prospective emissions reduction project developers (page 33, paragraph 68).

The activity participant can assess the susceptibility of its project to corruption by comparing it to the host country regulations regarding corrupt activities. However, if those regulations are vague or non-existent or if the enforcement of the regulations is inconsistent, the activity participant may not know how to respond to these two questions. If the role of the relevant DNA in the SD Tool is not described, the activity participant may not consult with that DNA prior to answering the two questions. The A6.4 SB cannot dictate how DNAs should investigate possible instances of corruption and when such cases should be prosecuted. But it can require that the relevant DNAs be involved in implementing the corruption principle.

In an Oct. 8 article, we suggested that the A6.4 should study and learn from the U.S. authorities’ investigation and both civil and criminal prosecutions of a project developer that had submitted falsified emissions reduction data to Verra, the global leader is issuing voluntary carbon credits, concerning 27 clean cookstove projects. In June, after conversation with the U.S. authorities, Verra suspended those projects and announced a forthcoming review of its cookstoves credit methodology. The number of cookstoves in an emissions reduction project is one indicator of achieving one Sustainable Development Goal in the SD Tool. On Oct. 9, Verra released its revised cookstoves methodology. On Oct. 21, Verra announced that it was laying off a quarter of its staff, which presumably leaves it with less capacity to verify emissions reduction claims of the projects on its credit registry.

We wrote in our article, “if COP29 negotiators want to sustain these [emission reduction credits] sales and investment in emissions reduction projects, they must not ignore the lessons of voluntary carbon market corruption.” Instead, the negotiators, and particularly the A6.4 SB, must frankly confront the possibility of corruption among participants in the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism. Otherwise, the market and credit integrity issues that have plagued voluntary carbon credit trading may be reproduced in the Article 6.4 mechanism, as experts commented in an Aug. 15 meeting of prospective carbon credit buyers and emissions reduction project investors.

A6.4 standards: Buying time to reduce climate catastrophes?

The challenges are many and great for the Article 6.4 mechanism to operate successfully, to contribute to significantly reducing absolute emissions to meet the Paris Agreement objectives. IATP hopes that our analysis of these three Article 6.4 documents contributes to a realistic appraisal of the challenges of building Paris Mechanism market integrity while the momentum towards climate catastrophe lays waste to the econometric projections of carbon markets as a source of significant climate finance. The A6.4 standards and framework for “continuous improvements” in carbon accounting methodologies responds to the Parties’ inability or unwillingness to phase out fossil fuels, as documented by increasingly dire climate science and climate modeling reports.

For example, a UN Environmental Program report released on Oct. 24, stated that under partial to no implementation of governments’ current greenhouse emissions reduction commitments, a 2.6-3.1 degrees Celsius (5.4 F) average global temperature increase by 2100 over the pre-industrial mid-nineteenth century baseline is projected. That latter increase would more than double the Paris Agreement goal of limiting average global warming to 1.5 C above the baseline. On Oct 28, the World Meteorological Organization reported that GHG concentrations (emissions minus their absorption by ocean and land sinks) reached record high levels in 2023. The WMO Deputy Secretary General said of the report, “Natural climate variability plays a big role in carbon cycle. But in the near future, climate change itself could cause ecosystems to become larger sources of greenhouse gases. Wildfires could release more carbon emissions into the atmosphere, whilst the warmer ocean might absorb less CO2. Consequently, more CO2 could stay in the atmosphere to accelerate global warming.” In such a grim future, methodologies to estimate a project’s risk of emissions reversal likely will be a futile accounting tool.

IATP devotes time and resources to analyzing Article 6.4 mechanism documents not because we believe the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism is the most effective way to reduce emissions and mobilize climate finance. We do so because despite myriad voluntary carbon market failures and the failings of the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism, Parties and private sector investors who own fossil fuel assets that quickly will become stranded assets support the Mechanism. Under Business As Usual scenarios, those Parties and investors and fossils fuel dependent industries, such as agribusiness, will suffer huge financial losses if emissions are reduced 42% by 2030 to align with achieving the 1.5 C Paris Agreement objective. Those Parties and investors have a stake in buying time for the A6.4 standards for emissions removal technologies and credits derived from them to become at least economically successful for them. However, if these standards and their “continuous improvement” results in a functional Mechanism, the selling of emissions reduction credits, recalibrated for ever larger and more frequent emissions reversals, will unlikely be able to demonstrate that the Mechanism has achieved the Article 6.4 d) aim: “to deliver an overall mitigation in global emissions.”

IATP’s preferred approach to Article 6 financing to reduce global GHG emissions

IATP as an individual organization and as a member of the Climate Land Ambition Rights Alliance (CLARA) has long favored the Paris Agreement Article 6.8 non-market approach to climate finance for direct investment in emissions reduction and adaptation projects. A recent CLARA paper outlined the launching of the Article 6.8 mechanism at COP28, including a web-based project investment registry platform. CLARA contends that the Article 6.8 mechanism more effectively and transparently contributes to each Party’s Nationally Determined Contributions to mitigation to achieve the Overall Mitigation in Global Emissions goal, a bedrock principle of Article 6. CLARA has proposed workshops to advance the implementation of Article 6.8, including one on innovative financing mechanisms (p. 7).

A May 2024 study of studies estimated at $8.5 trillion the annual global finance that would be currently required to reduce emissions to achieve Paris Agreement global warming and emissions reduction objectives. The most optimistic voluntary carbon market econometric study, by Bloomberg NEF, projects the global transaction value, under a “right rules” scenario, to scale up to $1 trillion annually by 2037. Only a small share of that projected transaction value will go to the countries in which voluntary emissions reduction projects are located.

In a September briefing paper for COP29, Oil Change International identified sources of rich country public funding for direct climate action projects that would amount to at least $5.3 trillion annually now. The briefing noted that $16 trillion was mobilized globally to combat COVID-19. We would add that the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank issued $29 trillion in ultra-low interest emergency loans to bail out reckless and insolvent global banks and their subsidiaries from 2007 to 2010. The mantra that “there is no money” to invest to avoid climate catastrophe is not about an absolute lack of money, but a tacit admission that it is politically easier to invest in just about any complicated global policy priority than to invest directly to prevent climate catastrophe.