Appendices referred to in the ANEC Profile

ACCI/MICI approach works at different levels, starting with soil improvement and conservation (oxygenation, mineralization, increase of organic matter, balance of microorganisms, etc.), plant (identification and characterization of key stages by crop, nutrient needs, etc.), biotic factors (pest and disease management), abiotic factors (measurement of time variables and their effect on crops, inducers of plant resistance, etc.), among others.

To implement these concepts, the following process is performed:

- Diagnosis and definition of production goals. (Physical chemical analysis, and MRI, molecular and atomic).

- Soil conditioning and seed selection.

- Oxygenation, massive induction of microorganisms, minimum tillage.

- Phenological characterization of the crop. (Requirement of units of heat and cold hours)

- Attention to the nutritional demand of the crop.

- Demand for nutrients per unit of production desired.

- Stocks, availability, complement, sources and efficiency of use. (State and mode of application, lunar moment of application and suitability of pH).

- Monitoring of crop stressors. (Meteorological, parasite, pathogenic, competition, etc.) and definition of thresholds.

- Integrated management of the burden (acquired plant resistance, induced plant resistance, biological control, use of biorracionales, management of competition for light, use of agrochemicals in extreme cases)

- Induction of growth promoters.

- Conditioning of ripening of the crop.

- Storage of grains in storage.

The forging part is fundamental to achieve the transfer of results so we consider the following actions:

- Theoretical - practical training:

- Workshops and training courses for field technicians.

- Workshops and training courses for producers.

- Permanent consultancies of specialists

- Stays of technicians in modules

- Visits and accompaniment to technicians and producers by specialists.

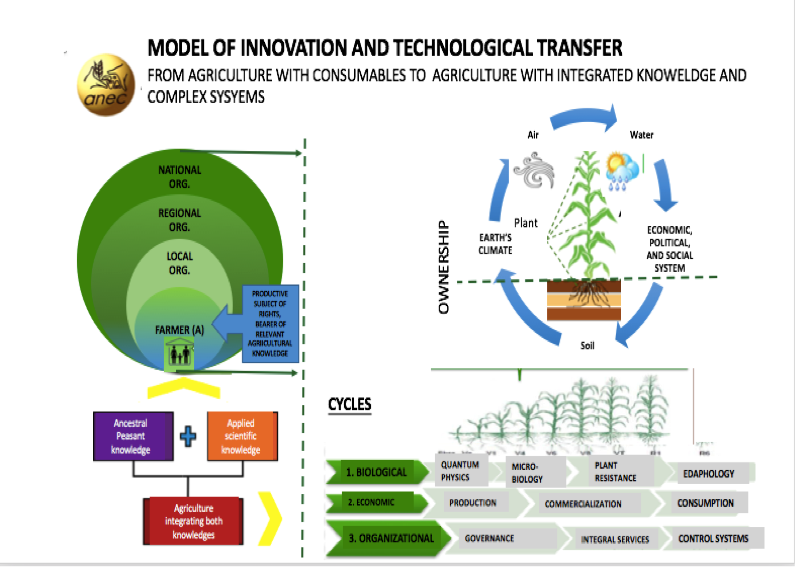

A. ANEC’s organizational model

Developing an organizational model that meets the needs of this diverse membership, and allows for decision-making and policy advocacy that amplifies their collective interests in national and international policy arenas is a challenge. There are conflicting interests and competing needs. Balancing between the business-like nature of farmer organizations (their need to be profitable), and ANEC’s overall socio-political objectives, requires navigation and democratic deliberation.

A decentralized governance structure helps the organization collectively work for better conditions for all its member farmers while simultaneously attending to their diverse needs. Clearly defined democratic principles and good governance practices (See further below, B & C.) combined with an interdisciplinary staff that works collaboratively to transmit information and coordinate spaces for dialogue and debate, helps ANEC build the capacities of local level leadership and membership to foster sustainable and equitable rural development processes.

Decentralization:

At the core of ANEC’s model is the local farmer organization. Local organizations are small businesses with socio-political values and responsibilities. The local organizations are called Empresa Comercializadoras Campesina, or ECCs, which translates as Peasant Commercializing Enterprises. Each ECC is its own legal entity and must conform to Mexican business standards, paying taxes, keeping records, and so on. In addition, ECCs adhere to a set of democratic principles and practices required of ANEC members, which include meeting regularly, making decisions democratically and transparently, and being accountable to their membership.

Local organizations are included in second tier, regional organizations called integradoras. Regional organizations also commercialize the harvests of local member organizations. They have a general assembly and an advisory where the leadership from local organizations meet and discuss everything from annual price forecasts, potential government subsidies, and regional and national politics and policies. Regional organizations are also meant to be involved in state-level advocacy.

The regional organizations (there can be more than one per state, depending on the size of the state and concentration of member organizations) are federated into the national association, ANEC.

ANEC itself has a general assembly with representation from local and regional organizations with a president, an advisory board, an Executive Director, and a national staff that coordinates five different program areas, which are:

- Commercialization: This area monitors markets and price trends, gives farmers advice about contract negotiations between a buyer ad the ECC, and helps negotiate national-level contracts to commercialize grain.

- Political Advocacy: This area is dedicated to advocating for public policies and programs to support members and advance a sustainable and just food system.

- Finance: This area provides micro-finance products including crop-insurance and credit and a savings-and-loans program. Trainings in financial literacy are also given to members.

- Organizational strengthening and support: This area supports members developing their capacity to run the business side of the ECCs, helping ensure that organizations are maintaining good records and being transparent about accounts.

- Production (ACCI/MICI): This area provides support for farmers transitioning towards ACCI/MICI through the development of infrastructure (like laboratories for soil testing) and the organization of trainings about agroecological science and practices.

- These different service areas were developed as a response to identified needs. Initially, ANEC had only three service areas; commercialization, advocacy, and organizational strengthening and support. “When we first started in 1995, facing the effects of NAFTA and the dismantling of national markets, our primary objective was to help negotiate better prices for farmers by organizing them and leveraging production at scale for better contracts.” (Toño)

- Similarly, ANEC’s forays into financial services, through Seguros ANEC and SofomANEC crop insurance and micro-credit funds1 were developed to alleviate member farmers’ difficulty accessing credit, and in response to generally ineffective and expensive crop-insurance programs. “Together with our members we realized that there were no decent options for credit and then no decent options for crop insurance and so we decided to get in the game” (José).

- ACCI/MICI was developed for similar reasons. ANEC had already been participating in government programs that provided local organizations with agricultural extension services in the past but ANEC had never provided technical support for production in a systematized or centralized way.

ANEC works with groups of organized farmers who work and learn collectively and who rely on one another for support when taking on the rather risky endeavor of trying a new production practice. The introduction of new agricultural practices was bolstered by the strong, trusting relationships cultivated by ANEC’s staff and tecnicos with members as well as the access members had to other services including capacity building. Lourdes Rudiño, a Mexican journalist and researcher who first wrote about ANEC’s forays into productive innovation, has argued that the increase in yields ANEC realized were because the productive innovation was grounded in ANEC’s organizational model. ANEC’s integrative approach to rural development is distinctive in Mexico and “goes against the current of individualism that is promoted in the public programs implemented in the agricultural sector in Mexico” (Rudiño, 3, 2010).

The combination of a strong organizational structure and existing pathways for transmitting information and fostering dialogue is essential to ANEC’s success in developing and scaling-out the ACCI/MICI approach.

B. ANEC’S PRINCIPLES AND VALUES

a. Economic organization with a social impact and environmental responsibility

b. Independence

c. Autonomy

d. Plurality

e. Self-management

f. Democracy

g. Subsidiarity

h. Justice, equity and solidarity

i. Transparency

j. Being proactive, innovative and constructive

C. ANEC’S MISSION AND CODE OF GOOD GOVERNANCE PRACTICES

- We work with devotion and stay committed to the mission, principles, values and organizational model of ANEC.

We are organized peasants who are committed to learning ANEC’s objectives, mission, vision, principles, values and organizational model, and we affirm our solidarity with them as well as our willingness to work diligently to fulfill the organization’s mandate while bearing in mind our organizational model.

- We are organizations at the service of and for peasants who take part in them, and for the women and men of the Mexican countryside.

We are economic organizations with a solid commitment to social and environmental well-being, made up of peasants who mainly produce basic grains, and we organize to work on our problems, needs and initiatives in order to acquire greater economic and decision power. We are dedicated to improving equity and the quality of life of our members, their families, their communities and the rural sector.

- We are autonomous, independent self-sufficiency and diverse organizations, and we govern ourselves according to democratic principles

We are organizations that are dedicated to and answer to our highest decision-making body, the General Assembly. We value and develop our autonomy and self-management abilities, and we do not depend on any external authority (e.g. political parties, peasant unions, governments, companies, legislators, etc.). We are diverse and respect the political, religious and sexual preferences of each member. We make collective and democratic decisions, through the General Assembly, Board of Directors sessions, and work meetings, in accordance with our interests and needs expressed in plans and programs, and employing methods, procedures and mechanisms that allow us to improve peasants’ governance in our organizations.

- Our management and operational structures are at the service of the organization.

ANEC’s organizational model regards the General Assemblies comprised of members of each organization as the highest authority, and according to this model we work with a management structure made up of producers, and our own professional managerial and technical structure, which must strengthen members’ self-management skills, and operate in strict compliance with their established mandates, principles & norms.

- We work towards the development of local strengths and capabilities.

We are committed to developing local organizational, technical and technological capabilities, and to sustainable economic development. To this end, we will promote the exchange of experiences at the local, regional and national level, and we will provide annual training and education programs in each organization, with a focus on equity, to promote training for local leaders, administrative staff, organization members and the technical team. This training will also facilitate the operation, duties and obligations of members, governing bodies and the technical-managerial team.

- We are committed to practicing sustainable and integrative agriculture that cares for nature and consumers

We strive to practice agriculture that safeguards soil, water and the environment and produces healthy food for consumers, combining peasants’ knowledge with scientific and technological knowledge. Our organization embraces the production chain comprehensively, from production to consumption, by including the by-products of members’ productive activity, and promoting the use and development of modern technologies while also being mindful of environmental sustainability and the integral development of communities and the environment.

- We are inclusive and we organize ourselves with an equity approach.

As inclusive organizations, we promote our growth by admitting all producers who wish to organize, as well as new organizations, that commit to adhering to ANEC’s principles. This also entails eradicating inequalities by developing mechanisms that promote the active and equitable equal participation of women and young people in the governing bodies of our organizations, in decision-making, and in each and every one of our activities.

- We practice and demand an honest, efficient and transparent administration in our organizations and we strictly comply with our accountability to organization members

The principles of democracy, justice and equality commit us and require us to conduct an honest, efficient and transparent administration in our organizations at both the individual and collective levels. Transparency regarding our accountability and access to consistent, accurate, sufficient and timely information of all organization activities is one of our most appreciated, fulfilled and mandatory practices.

- We build and use standardized management methods and systems and commit ourselves to an annual comprehensive management audit.

All our organizational and resource management processes are carried out using specific systems and methods that ensure efficiency, democratic governance and transparency for all organizations and members. In order to achieve greater control of operational and administrative practices, we accept and promote the implementation of strategic plans, as well as a comprehensive audit of annual management as a basic procedure of self-regulation.

- We mobilize to demand our rights and stand in solidarity with other fair causes, and to influence national and rural sector public policies.

In defending our principles, values and objectives and by building transformative citizenship, we commit ourselves to mobilize in a legal and peaceful manner in order to demand our rights and advocate for our demands and proposals, as well as stand in solidarity with other fair causes in Mexico and in other countries. We analyze and propose public policies that are favorable to the development and sustainability of peasants’ advocacy and the sustainability of the Mexican countryside, maintaining our independence and political autonomy from external agencies.

D. CODE OF MINIMAL GOOD PEASANTS’ GOVERNANCE PRACTICES

Operation of organizations’ governing bodies

- Establish the General Assembly as the highest governing and decision-making body of the organization in the statutes and in the conscience of the members, as well as ensure it in practice, and that the main actions, programs, projects, management, credits will be approved by this authority. These decisions will determine the organization’s future direction and will incorporate the mission, principles and heritage of organization members.

- Hold General Assemblies, at least one bimonthly, with member producers from local grassroots organizations, and with delegates for organizations comprised of legal entities, in accordance with annual calendars approved in the General Assembly and known to all.

- At each General assembly, a memorandum of agreements must be drafted and recorded in the corresponding minutes book, ensuring proper follow-up and compliance of agreements by the Board of Directors and management.

- In the integration of the Board of Directors or Administrative Board, women and youth must be elected and participate in at least 30% of positions to ensure and promote their representation and equal participation in decision-making. Likewise, External Directors will be included in ANEC’s national initiatives and those of organizations with larger-scale operations.

- Ensure the attendance of the majority of members (more than 60%) in General Assemblies by means of prior announcements and effective campaigning.

- Conduct at least one monthly session with the Board of Directors. Each director will have information about the duties, responsibilities and faculties of his / her function, and will sign an agreement committing to these prior to discharging his/her duties.

Transparency and accountability

- The Board of Directors or Administrative Board must ensure effective communication with the entire organization and each of its members. At each assembly, it will present a complete, accurate and up-to-date report showing the financial position of the company, as well as the plans and activities it is carrying out and intends to carry out, and this report is to be reviewed and analyzed by members.

- The Manager shall issue monthly financial and operational reports, which shall be reviewed by the Board of Directors and the Supervisory Board and approved, where appropriate, by the General Assembly of Members.

Self-regulation

- All operations carried out in the organization must be submitted to a registration and accounting process that applies commonly accepted standards, procedures and systems. They will have updated and regularized their control systems and will use the instruments developed by ANEC, in order to standardize accounting and financial criteria.

- The Board of Directors and the Supervisory Board or Commissioners will be responsible for promoting an annual internal and comprehensive management audit (administrative, accounting, fiscal and financial), whose results will be known to the Board of Directors or Administrative Board and the General Assembly.

Planning

The Board of Directors will be responsible for promoting a strategic five-year plan for the organization, and will annually evaluate improvements or setbacks to correct mistakes or negative attitudes in time. And for it, a General Assembly of Balance and Programming will be held to approve, where appropriate, the operational and financial report of the Board of Directors and of the Management, as well as to define and approve the operational program for the following year.

Building Local Skills and Training

As part of the strategic plan, a training plan will be defined each year, aimed at strengthening the capabilities of each and every one of the organization’s members, especially women and young people, and strengthening their respective roles as well as their respective projects: members, the administrative board, the managing director, and technicians by area.

[1] While guided by the principles and objectives of the national organization, ANEC’s credit fund, crop-insurance service, and savings and loans initiative are intended to operate independently and autonomously from ANEC.

(or Why ANEC’s approach is the “agroecological transition ANEC’s farmers need”)

ANEC’s national staff and regional and local tecnicos work collaboratively to promote ACCI/MICI by applying the four best practices, rooted in its mission and principles, that are especially essential to ANEC’s success developing and promoting ACCI/MICI, listed below.

1. MEETING FARMERS WHERE THEY ARE

ANEC meets farmers where they are, introducing them to the practices and techniques of ACCI/MICI that address their most pressing needs and adapting these techniques to their capacities. Most farmers who are applying ACCI/MICI practices are determined to lower costs and increase profits. Other farmers want to eliminate the use of toxic pesticides because of chronic health problems and others want to be less dependent on volatile prices of inputs. Depending on the motivations and local contexts—like if farmers receive state subsidies for fertilizer or pesticides—ANEC’s staff will strategically select elements of ACCI/MICI that address farmer’s motivations. For example, if farmers are interested in ACCI/MICI to reduce costs and they do not receive subsidies for fertilizers, ANEC will often start the transition by introducing farmers to the organic composts and vermiculture extracts. Once farmers experience a reduction in cost by reducing application of commercial fertilizer, ANEC can introduce other ACCI/MICI approaches.

ANEC’s member farmers have diverse capacities and capabilities—some farmers have retained knowledge of traditional farming practices but most have become accustomed to a model of agriculture that is formulaic. Using farmers’ knowledge and the production techniques farmers are familiar with, which in many cases are derivatives of green revolution production practices, ANEC introduces members to alternative practices. Worm compost and microorganisms might come in packaging or “doses” that are similar to conventional inputs, making their application less daunting for a farmer who is just beginning to adopt ACCI/MICI. Some farmers are interested in developing their understanding of the complex ecological interactions occurring on their land and others want to be given simple instructions. For the latter, ANEC has to work harder to engage these farmers in the collaborative and co-innovative agricultural processes that make it possible to maximize productive efficiency and sustainability.

ACCI/MICI is premised on the co-innovation that happens between farmer and scientist or tecnicos, what ANEC refers to as the dialogue of knowledge1, or the interaction of a farmer’s praxis-based knowledge with a scientists or tecnicos theoretical knowledge. The combination of these different kinds of knowledge results in an approach to farming that is uniquely adapted to a farmer’s land, an approach, which maximizes yields while minimizing waste. Farmers who have become accustomed to a one-size-fits-all approach to production often find that ACCI/MICI requires much more work and steep-learning curve. ANEC helps minimize these burdens by making farmers feel that staff and other farmers are available to support them. Moreover, national, regional and local staff develops and exchanges techniques for helping different farmers build their capacities. Some local tecnicos have created names for ACCI/MICI microorganisms or pheromones that help farmers understand what the “input” does. “ Instead of the opaque industrial names of chemical inputs—like the glyphosate-based herbicide Roundup—we have a combination of microorganisms that we call “strengthen-root” or “flower-aid” so that when our local tecnicos recommends the microorganisms he or she can share the scientific names of the organisms while helping farmers learn their different functions.” (Don Bacilo). Finding ways to adapt to farmers unique motivations and capacities allows ANEC to meet their diverse membership where they are and engage them in an agroecological transition.

ANEC’s approach to working with member farmers has always been pro-active, staff are constantly visiting farmers, organizing workshops, presentations or visits, where one organization hosts another. These interactions create spaces for discussion, debate, and information exchange and allow ANEC’s staffs stay in-tune with local realities. This practice has been instrumental to the development and scaling of ACCI/MICI among member organizations.

Fostering Dialogue-

The dialogue of knowledge that occurs in the expansion of ACCI/MICI is a process of co-discovery and co-innovation. Many of the tecnicos are learning about agroecological techniques and coming to understand ecology, soil science, and microbiology for the first time. Tecnicos are learning about ACCI/MICI at the same time as the farmers that they are meant to advise and accompany.Even the scientists that ANEC collaborates with may have a theoretical understanding of the way that agricultural systems interact but they are testing, and therefore learning from, the theories that farmers are putting into practice in their fields. “ACCI/MICI started out as mostly theory that the scientists thought would work but they need us and the farmers to test it in practice, to see how theories play out in different contexts.” (Ing. Toño).

ANEC provides farmers with information about every aspect of farming systems and creates ample spaces for dialogue and for farmers to mutually support each other. These spaces allow for co-learning and empower farmers, giving them ownership over new ideas and approaches they can use to improve production practices. In order to foster this kind of space, where farmers and tecnicos and scientists can exchange information and collaborate, there needs to be a strong foundation of trust and mutual respect. ANEC has fostered strong relationships with farmers by recruiting and retaining staff, especially tecnicos that share values. In addition to getting training in the ACCI/MICI approach, every new recruit is trained in ANEC’s democratic principles and practices. This training helps mitigate traditional power hierarchies between agriculture engineers, extension agents, and small-farmers.

“A lot of agronomists come out of school and think they know everything, they are used to traditional hierarchical relationships between tecnico and farmer where the farmer doesn’t question the tecnico’s knowledge and there’s no accountability of the tecnicos to the farmer. We recruit and train tecnicos to be humble and to respect and value farmer’s experience and their knowledge. Our organizational structure also helps because tecnicos salaries are determined by the local organizations, which makes tecnicos accountable to their farmer organizations rather than to a government extension program.” (Beti)

A Different Kind of Technical Support/Agricultural Extension

An integral part of ANEC’s success with ACCI/MICI is the recruitment and retention of tecnicos who demonstrate their capacity to help farmers solve problems. ANEC helps local organizations recruit and train tecnicos that have certain characteristics, including humility and appreciation of small farmers and an interest in learning about the ACCI/MICI approach. Tecnicos play a crucial bridging role in the dialogue of knowledge as well as helping transmit information back to ANEC’s national staff and also serving as entry-points for ANEC’s socio-political work, strengthening the democratic practices and capacities of local organizations.

The tecnicos ANEC recruits do not have the same profile or experience of a traditional agricultural extension agent. The majority of ANEC’s tecnicos do not have degrees in agronomy. Of the 15 different local tecnicos interviewed, only 3 had degrees in agronomy. The others ranged from no formal degrees to systems engineering, biology, and some younger tecnicos had studied agroecology. ANEC’s staff member, José Atahualpa, explained, “I actually think it’s harder for a traditionally trained agronomist to be an effective tecnico in ANEC because their schooling teaches them completely different approaches to production… also, they usually think they already know everything and don’t have the humility or curiosity to engage in learning more.”

The tecnicos that stay with ANEC’s organizations are committed to the socio-political values of ANEC.“ They don’t do it for the money, that’s for sure” (Don Simon, Nayarit) said one of the farmers. Tecnico incomes are known to be inconsistent; many of the tecnicos interviewed were owed 2 months of back pay because of delays in government programs that subsidize their incomes. More than ¾ of the tecnicos were farmers themselves and were applying an ACCI/MICI approach to their own land. Often times they are from the community, some times they are sons or daughters of a member farmer. This is a deliberate strategy employed by ANEC “we want to hire more sons and daughters of farmer members, they already have a relationship with farmers in the community and they are invested in the community’s well-being” (Jose).

ANEC is also attempting to hire women tecnicos. The two newest hires were young women from rural communities who had studied agroecology at the Chapingo Autonomous University. Since ANEC respects local organization’s autonomy, it cannot impose quotas for women or force local organizations to elect women leaders. However, since ANEC helps cover part, or all, of most tecnicos salary, ANEC can help influence recruitment and advocate for women and youth to be in positions of influence in a local organization.

Recruiting and holding on to effective tecnicos is a constant struggle for ANEC. It is difficult for local organizations to be able to afford salaries year-round and it has been difficult to find tecnicos who are willing and interested to attend the intensive workshops and training in ACCI/MICI required of all staff. ANEC has attempted to invest in building the capacity of younger members and the sons and daughters of members, subsidizing their training and, when it can, subsidizing the income of tecnicos that apply ANEC’s principles in practice and that have been able to create strong, trusting relationships with farmers. When ANEC identifies a tecnicos that embodies its democratic principles and that works collaboratively with farmers, the staff will go to great lengths to retain that person. Sometimes this means transferring them to another service area until the local organization or ANEC can find the resource to pay their salary again. The collaboration between staff at local, regional and national scales increases ANEC’s ability to adapt its approach and respond to local contexts. It also enables ANEC’s national staff to design and advocate for programs and policies at a national-level that support their diverse membership

2. LOOK FOR ENTRY POINTS

ANEC relies on strong channels of communication between local, regional and national staff and leadership to identify key moments to introduce ACCI/MICI and key actors that can help promote ACCI/MICI. Key moments for introducing ACCI/MICI are often moments of crisis or transition, when there is a climatic event or farmers have struggled to make production profitable or when there is a transition in leadership. ANEC also identifies key actors, farmers, leaders and/or local tecnicos that are interested in learning about, and applying, the ACCI/MICI approach. These key actors are seen as catalysts for change in their organization and community and ANEC invests in their capacities to transmit knowledge to other farmers.

A number of farmers interviewed mentioned their first introduction to ACCI/MICI happened after a particularly devastating weather event (like a hail storm) or a crisis moment, where they were facing the prospect of abandoning production. A tecnico from Nayarit posited that crisis was key, a common entry-point for ANEC to introduce ACCI/MICI and start convincing farmers of the virtues of agroecology.

Many farmers also recounted that their first interaction with the tecnicos were around parcels of land that they had essentially given up on. Don Nacho in Jalisco described his first: “I was about to mow down my whole sugar cane crop because I had tried everything and I went to go see Inge2Pancho [local tecnico] and he convinced me not to, hold off he said, let’s try a few of the microorganisms and oxygenate your soil….and it worked! Now I have him come help me all the time…Inge, if my harvest comes out well this year, it’ll be because of you. I’ll owe you a beer.”

The local tecnicos in Jalisco, Inge. Toño and Inge Pancho mentioned that Don Nacho had been a very critical of the tecnicos and a skeptical member of the local organization, The Union de Ejidos Ex-Laguna. “He’d never asked us for help before a few years ago and he rarely attended meetings. That’s changed since he has started applying ACCI/MICI.” (Inge Pancho.) The results farmers have seen through the application of ACCI/MICI has sometimes helped strengthen local organizations, showing farmers the benefits of working collectively to address both productive and political issues.

“Sometimes we can influence an organization, spur change, by directly appealing to the social objectives we aim to achieve, other times farmers are interested in the agricultural support or the economic services we offer and, gradually, we can engage them in our social project or our agroecological project. All of these are entry-points that help us advance our objective, lead to local organizations adopting the ANEC model, which is premised on participatory democracy, and result in strong agrarian citizens.” (Victor)

Every organization participating in ACCI/MICI had at least one identified key actor, which could be a local tecnico, farmer or leader of an organization. The transition process was faster an organization had more than one key actor-- when leadership, technical staff and membership are all onboard with adopting ACCI/MICI. However, identifying even just one advocate for ACCI/MICI at the local scale, one person who is capable of transmitting the benefits of ACCI/MICI practices by demonstrating its results on their own land or by accompanying farmers in its successful implementation, can help foster the transition process.

3. USE EXISTING RESOURCES

The diverse key actors involved in the ACCI/MICI transition reflects the wealth of existing knowledge and capacities present in each of ANEC’s member organizations. ANEC’s approach to promoting ACCI/MICI leverages local human and ecological resources, like the rich agro- biodiversity present in Mexican rural communities, to accelerate farmers’ transition to more sustainable and resilient farming systems. Some of ANEC’s key actors are “model farmers”; members that have been using agroecological practices for a long time and have a deep place-based knowledge. Don Javier from Jalisco is one of these farmers. Even before joining ANEC he was using organic practices for farming corn, beans and squash. “I just don’t like chemicals, I’ve always thought they were bad,” he explained as his reasons for avoiding conventional industrial paquetes. Don Javier has been performing his own agroecological experiments, selecting from his heirloom seeds, and developing a native corn that ANEC is using in an experiment it currently facilitating in partnership with researchers from the Autonomous University of Chapingo.

The experiment is comparing five different corn seeds and testing them for their resistance to ecological shocks and their yield potential. Two of the seeds are native heirloom seeds cultivated and selected by Don Javier and another of ANEC’s model farmers in Chiapas. These two native seeds are being compared to three commercial hybrid varieties. The experiment is being conducted in four different states and being monitored by a team of tecnicos, leaders and farmers from local organizations. Collaborating researchers from Chapingo, who will also be analyzing the results, designed the experiment, which also compares conventional vs. ACCI/MICI production practices. This experiment is part of ANEC’s initiative to improve native seeds as a means of further reducing costs (seeds represent about 20% of farmers’ production costs) and promoting agrobiodiversity. The investment in native seeds is also part of ANEC’s strategy to increase local farming systems’ resilience to climate change. This seed experiment exemplifies the dialogue of knowledge that grounds the ACCI/MICI approach to farming. Moreover, it demonstrates ANEC’s use of existing resources, the knowledge and capacities of its diverse membership, to promote and innovate sustainable farming practices.

4. SHARE INFORMATION

While ANEC has some model farmers, the majority of ANEC’s members have been integrated into a state-subsidized, agro-industrial system. “We’ve become dependent on paquetes, the seeds and fertilizers and chemicals that the state used to give us for free, and we’ve forgotten all the conocimientos (knowledge and practices) of our forefathers.” (Don Simon, Jalisco). In addition to not possessing the kind of place-based ecological knowledge that agroecological farming needs to be effective, a lot of farmers do not have the confidence in their capabilities. By creating mechanisms for knowledge exchange and mutual support, ANEC empowers farmers to engage in what may seem like a risky or daunting transition to a different farming system.

Beside from the regular (sometimes-monthly) workshops led by allied scientists that ANEC organizes for farmers and tecnicos to deepen their agroecological knowledge, ANEC also fosters information exchange among regional farmer groups. ANEC organizes regular visits where farmer’s organizations that may not be convinced of ACCI/MICI can see the parcel of other farmers applying ACCI/MICI. This farmer-to-farmer learning technique is not unique to ANEC but it is essential to the transition process. ANEC and tecnicos have also helped farmers set up Whatsapp text-message groups where they can share information and ask questions of other farmers and tecnicos from other regions. “ I sent a message to the group asking about how they were dealing with a pest I’d started to see on my sorghum crop and I got a several responses of things other farmers had tried. Any time I have doubts or questions, I send a message to the group and I get responses almost immediately from a tecnicos or another farmer” (Don Juan, Chiapas)

In order to increase farmer’s information about weather and pest risks, ANEC is in the process of developing a platform that will send farmers alerts about upcoming climatic events or pests that are affecting agricultural systems in the area. This project is in collaboration with researchers from Mexico’s National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP). Dozens of local farmer organizations are receiving equipment to set up meteorological stations that will feed information into the platform. The objective of the project is to alert farmers in advance of biotic or climatic threats and to accompany the alerts with recommendations of what to do.

The practices outlined above describe how ANEC fosters a transition to ACCI/MICI amongst its diverse members ANEC has developed its approach, and the practices of meeting farmers where they are, fostering dialogue, looking for entry-points and sharing information, over the course of 22 years of work in rural communities. These practices have been essential to all of ANEC’s program areas. In its efforts to support farmers in commercialization ANEC is constantly building local organization’s capacities to negotiate fair contracts and sharing information about fluctuations in grain prices. The organizational strengthening and support program area helps local organizations establish transparent accounting practices and offers training in leadership and democratic governance. Each organization decides what services and support it wants from ANEC. ANEC empowers farmers with the information they need to help articulate solutions to the complex political, economic and ecological obstacles they face but, ultimately, ANEC respects local organization’s autonomy.

Multiple representatives from each organization are invited to attend ACCI/MICI workshops. The workshops are given by allied scientists that ANEC have identified for their capacity to work with farmers and transmit complicated scientific concepts to farmers. These workshops are intensive and participatory, often entailing field visits and practical applications of skills. They cover all aspects of the farming system, starting with soil health, soil improvement and conservation (oxygenation, mineralization, increase of organic matter, balance of microorganisms, etc.), and then helping farmers understand plant physiology (identification and characterization of key stages by crop, nutrient needs, etc.). Workshop participants also develop their capacity to interpret and address biotic factors (pest and disease management), and abiotic factors (time, different ecological cycles).

Every season, tecnicos help farmers design a farm management plan. Using meteorological data, soil analysis and data collected from the previous year, these plans help farmers set production targets and track the growing quantity of organic matter or the nutrient levels of their soil. Tecnicos also help farmers establish record keeping systems to monitor crop development. The plans help tecnicos and farmers implement and track the results of an ACCI/MICI approach by systematizing the record keeping and monitoring needed to respond to climatic or biotic threats to a harvest.

Respecting local organizations’ autonomy, while also advising them, empowering them with information and knowledge to make better decisions, is how ANEC has fostered strong, trusting relationships with many rural communities in Mexico. Fostering local ownership over processes of rural development has been essential to the ANEC’s success in all of its different initiatives, especially the development and scaling-out of ACCI/MICI.

[1] Dialogo de Saberes is a term used by Victor Toledo and other agroecologists to refer to

[2] Inge, short for Ingeniero, or engineer, is a term of respect that farmer use for tecnicos. The term typically refers to someone who has a formal degree in agronomy but many farmers refer to staff or other farmers with extensive knowledge as Inge to show respect.

- ACCI/MICI Results in 2016: Results gathered from various pilot parcels administered by participating local organizations where ACCI/MICI was applied to one-half of parcel and the other half left as control.

Corn

- 30% increase in output per hectare, 6.59 to 8.66 toneladas por hectárea

- Reduction in costs 30% of production from $2,912.71 to $2,000.14 per ton

- 60% increase in profits from $5,538.14 to 8,905.63 pesos per hectare

Sorghum:

- 30% increase in yields from 3.40 to 4.75 tons per hectare

- 28% reduction in cost from $3,138.36 to $2,441.71 per ton

- 600% increase in profits from $686.00 to $4,252.90 pesos per hectare.

Sugar Cane:

- 40% Increase in yields from 100 to 140 tons per hectare

- 60% Reduction in costs from $398.73 to $147.96 pesos per ton

- 265% average increase in profits per hectare from $27,926.90 to $74,205.00.

The Transition towards an ACCI/MICI approach to farming contradicts/ conflicts with many agroecological ideals. ACCI/MICI does not place the same emphasis on crop diversification as other agroecological approaches to farming. While ANEC mentions the benefits of diversifying crops as a means of promoting ecological equilibrium and diversifying livelihoods in its ACCI/MICI workshops, it is not a priority-area. Most of ANEC’s farmers grow 2-3 crops commercially and have not yet been convinced of the benefits of diversifying production. Some model famer’s still practice milpa agriculture, planting corn, beans and squash together. When this intercropping occurs, it is usually for household consumption. Currently, it is difficult for farmers using agroecological techniques to compete in a conventional market. Since ANEC was founded as an organization that helped farmers commercialize their harvest in a conventional agricultural system, ANEC will likely have to continue to make adjustments to its organizational and productive model to foster diversification of crops. Continuing advocacy efforts that promote fair food systems, that acknowledge the multiple social and ecological benefits of investing in small-scale farmers, could help.

The localization and regionalization of food systems is another area ANEC could dedicate more time to. Selling locally, and cultivating stronger local and regional economies, is something ANEC talks about but has not been able to make much progress on. This may be because it requires state and municipal engagement and there is not much buy-in from Mexican local and regional governments.

ANEC is a member of a national campaign, called Valor al Campesino, which brings together other farmer organizations, civil society and researchers to advocate for policies and programs that support small farmers. As part of this initiative, ANEC has participated in discussions about fostering Community Supported Agriculture, linking urban communities to rural communities, and providing a reliable market for diverse, sustainably produced crops. Without a significant shift in Mexico’s national agricultural policy, though, ANEC and allies efforts will take more time.

Food security, and measuring the impact of ACCI/MICI on local food security, is something that ANEC has not explored. This is possibly because since all of ANEC’s members are commercial farmers, there is not much discussion about how much of the food produced is eaten. It is clear that many farmers to save some of their harvest for household consumption, however. ANEC implemented a pilot project, in partnership with Oxfam Mexico, which promoted diverse back-yard gardens as a means of increasing food security and engaging women in their organizational work. The pilot program had some success but it was never scaled-up beyond Chiapas. It would be useful to collect baseline information about ANEC’s member’s food security and to measure how adopting ACCI/MICI might affect household food security.

One of ANEC’s biggest challenges in the next five years will be the inclusion of youth and women into their organizational structure. Rural communities everywhere are struggling to find ways to encourage youth to stay and practice farming. Integrating youth and women into decision-making processes, and giving them the opportunity to learn about ACCI/MICI, is key. One of the reasons ANEC has lower participation of women and youth is because women and youth are not typically land-owners. While ANEC has addressed the need for agrarian reform in its political advocacy, internally it has no explicit strategies to include non-landholders. ANEC’s experience promoting ACCI/MICI has resulted in some promising cases where jornaleros, the day laborers that do much of the agricultural labor in rural communities, have been inspired and encouraged to rent their own parcels and apply ACCI/MICI. In both Michoacán and Guerrero there are cases of farmer organizations supporting jornaleros (usually young men) by giving them access to microorganisms or worm compost on credit. “We have seen how ACCI/MICI approaches work and result in higher yields at lower costs by managing other farmer’s land. It made us this that we could actually make a profit using ACCI/MICI on rented land and we did.” (Jornalero interviewed in Michoacán)

There are numerous exciting initiatives and examples of inclusion that could help ANEC develop more comprehensive strategies for engaging youth and women. However, ANEC needs to invest time and energy identifying and systematizing these initiatives if it is effectively going to address gender equity and youth exclusion. Currently, women represent only 20% of membership overall. Only 16% of ANEC’s farmers participating in ACCI/MICI are women. ANEC has some promising initiatives, like it favors the recruitment of women hires and all the new technical hires in the last year have been young women. ANEC has also piloted a number of programs to involve women (member’s wives) in the ACCI/MICI approach. For example, women members were supposed to be trained in running the biofabricas. In one of the ECCs in Nayarit, women are in charge of producing microorganisms and managing the worm compost production. While there are various cases of women in leadership roles or women participating in the ACCI/MICI transition, women and youth inclusion is not systemic and no initiatives to include women and youth have been scaled-out through regional or local organizations.

ANEC’s central leadership recognizes that inclusion of youth, women and non-landholders is a problem. “We were founded by mostly older male campesinos and ejidatorios1 we haven’t yet been able to find the right entry-point or pathway for engaging our membership on the issue of gender equality…it’s important to us but we don’t know how or what to do.” (Victor) It could be fruitful for ANEC to partner with other civil society organizations that have more experience with youth inclusion and gender mainstreaming. Strategic partnerships could help ANEC identify obstacles to inclusion and potential entry-points for engaging women in decision-making and productive processes. An initial diagnostic, analyzing how women and youth currently contribute to agricultural production, would be key. Unfortunately, little is known about women’s role in agricultural systems in Mexico and more studies are necessary. It is likely that women and youth possess unique knowledge about local agroecosystems that could enhance the ACCI/MICI approach.

There are various aspects of ANEC’s model that fall-short agroecological ideals however, when put into context, the strides ANEC has made is laudable. Mexico’s small farmers face numerous political, economic and ecological obstacles to sustainable rural development. For the last 22 years ANEC has been at the frontlines, advocating for political transformation while simultaneously helping farmers survive the dismantling of agricultural support systems, and piece-together an approach to sustainable farming that is adapted to their needs and capacities.

[1] Ejidatarios are farmers who received or inherited land through Mexico collective ejido land tenure system.

Below the transition process of three different local organizations is examined. These mini-case studies highlight the different entry-points used to introduce ACCI/MICI principles and practices and the key actors involved in promoting ACCI/MICI.

When organizations are less collaborative and horizontal in their decision-making processes are implementing ACCI/MICI productive techniques with building local farmer’s capacities or fostering a dialogue of knowledge, farmers are less empowered and have less ownership over the transition. The first case study examines one of these organizations, La Union de Ejidos Ex-Laguna in the state of Jalisco.

“One of our organizations in Chiapas still negotiates for paquetes [technology packages delivered by government agencies that include free or subsidized commercial inputs]. We’ve had a number of conversations with them about this practice. We’ve said ‘look guys, you don’t need to do that. It doesn’t help our political objectives—to transform the current food system. Also, it makes it more difficult to promote ACCI/MICI among members if they’re getting free chemical inputs,’ but we have to understand that and respect that that’s where that organization is at in its evolution. Perhaps their local situation and context requires it. Perhaps their membership expect leaders to behave this way and it’s still what leaders need to do to respond to member’s needs. We have to respect their local autonomy. All ideas and initiatives have to be owned/appropriated by the local organization, otherwise, in the long-run, they don’t work” (Victor).”

La Union de Ejidos was formed over 40 years ago. It is one of ANEC’s oldest member organizations and presents an interesting case of an organization that has successfully scaled certain agroecological practices but not managed to catalyze a holistic agroecological transition among member farmers. This seems to be a result of weak democratic governance and lack of buy-in from leadership.

Two extremely committed tecnicos, Inge Pancho and Inge Toño, are the key actors that have been largely responsible for the adoption of ACCI/MICI practices by members of the Union de Ejidos. These two tecnicos are both farmers and both have applied an ACCI/MICI approach to farming to their own land, using their own parcels as demonstration plots. Inge Pancho and Inge Toño have been limited in how they can introduce farmers to ACCI/MICI as organizational leadership is not supportive of ACCI/MICI and expects the tecnicos to provide traditional extension services. Instead of farmers participating in ANECs workshops and trainings, farmers rely solely on Inge Panch and Toño for help. As a result, farmers do not have a deep understanding of the science behind the ACCI/MICI practices and “inputs” the tecnicos had prescribed. “The Inge gave me this product, what was it called? Microorganisms! Yes! And it worked great!” (Don Simon). The farmers interviewed referred to ACCI/MICI inputs (microorganisms and worm compost) as a different kind of paquete. While they understood that these alternate paquetes were cheaper and more sustainable

Replacing conventional technical packages with more sustainable alternatives is neither the objective of ACCI/MICI nor agroecology. Introducing sustainable inputs can mitigate the negative impacts of conventional agricultural practices, however, it does not compare to a farmer learning to read and respond to their unique agro-ecological system. While ANEC is not interested in replacing current industrial paquetes with more sustainable inputs, it recognizes that each local organization has to start somewhere.

ACCI/MICI is a process that intends to change farmers’ approach agriculture. ANEC has to respect local organizations’ approach to introducing ACCI/MICI and work with who and what is available. In cases like the Union de Ejidos, ANEC will need to continue looking for other entry-points, possibly waiting for a transition in leadership, and work to create opportunities where for exchange and dialogue, generating buy-in from the Union’s member farmers and supporting the two tecnicos who are currently promoting ACCI/MICI.

Asking questions about why ANEC has not worked with the Union more closely to strengthen governance practices and foster ACCI/MICI revealed tensions and conflicts among staff, membership and leadership about the organization’s affiliation with ANEC. Half of the membership would like to be more affiliated with ANEC but the Union’s current leadership is affiliated with Mexico’s ruling political party. Recently, the Union went through an economic crisis as a result of an untimely investment. The state government of Jalisco supposedly offered the Union financial support on the condition that the Union took some distance from ANEC. This is likely because of Victor Suarez’s, ANEC’s Executive Director’s, known affiliation to an alternative political party.

ANEC, as an organization, does not have formal party affiliations. However, Victor Suarez, has held political office and is a recognized figure in the Mexican political landscape. Victor’s political affiliations do not implicate member farmers’ affiliations. In numerous interviews, farmers listed the fact that ANEC is not linked to a political party as one of the reasons they choose to affiliate with ANEC as opposed to other Mexican peasant organizations. “ ANEC has always helped us out and never asked us to show up to a certain politician’s rally or to vote for anyone. All of us here [in this organization] are affiliated to different political parties. This has never been an issue.” (Don Roberto, Chiapas.)

The transition towards ACCI/MICI will be slow until there is more buy-in from member farmers and leadership. ANEC works to support the key actors currently promoting ACCI/MICI and depends on these actors to share information about progress and other potential entry-points for promoting better governance and production practices.

“Organizations have to do what they have to do to survive, times are tough, we respect that. All we can do is maintain the dialogue that we have with them right now through ACCI/MICI and hope that there will be an opportunity to re-engage with the organization about democratic principles and practices at a later point.” (Victor)

There are two regional organizations in Chiapas that are involved in the ACCI/MICI transition. One of the organizations is a network of indigenous farming communities called Totikes. Totikes farmers have small parcels of land and practice more subsistence agriculture than the other organization, Red Chiapas. Red Chiapas is made up of commercial farmers who do not identify as indigenous. Totikes has been involved in the ACCI/MICI transition for longer, however the leader of the organization has been less supportive of ACCI/MICI in the past. The primary catalysts have been young tecnicos and a few model farmers. Juliana, one of the young tecnicos is a daughter of a farmer member and is emerging leader in ANEC. She, and two model farmers, are the key actors that attend the ACCI/MICI workshops and promote ACCI/MICI to member farmers

Red Chiapas is an interesting case because, unlike in other organizations where farmers were primarily motivated to integrate ACCI/MICI practices to reduce costs, farmers in Red Chiapas were drawn to ACCI/MICI because of collective health concerns over pesticide use. With RedChiapas, farmers reported little to no savings or increased yields. Rather, the impacts of ACCI/MICI were improved conditions for themselves and their families. Several farmers mentioned cases of intoxication from pesticide application. The majority of farmers had only applied ACCI/MICI techniques having to do with pest management. During the field visit, ANEC’s national staff was leveraging the successful experience reducing pesticide use to encourage members to begin applying other ACCI/MICI approaches. Specifically, ANEC’s staff was introducing the idea of producing and applying organic composts and worm fertilizer. RedChiapas famers were eager to experiment with a different ACCI/MICI practice because they had seen results using an ACCI/MICI approach to pest management.

The regional organizations in Chiapas have not invested in scaling vermiculture compost production to the same degree that other organizations have. This may be because the state government of Chiapas continues to distribute paquetes that include commercial fertilizer for free. It has been difficult to encourage farmers to invest labor and time into making their own compost when they receive free industrial fertilizer. Still, ANEC’s tecnicos and staff have continued to engage members in discussions about the benefits of organic compost and the importance of soil fertility. This year, there was less fertilizer allocated through state programs, which offered ANEC an entry-point. Over the course of the visit to RedChiapas there were conversations about getting worm compost extract from ANEC’s member organizations in Michoacán to test on a few parcels and explore the possibility RedChiapas investing in its own worm-composting infrastructure.

There are three farmers’ organizations in Nayarit that have worked together and been some of ANEC’s pioneers in the development of the ACCI/MICI approach. They were the organizations that were testing organic practices in 2006, before ANEC decided to invest in developing an agroecological approach to farming and are by far the furthest along in the agroecological transition. The organizations— San Pedro Lagunillas, La Moderna and Tecuala—are small but have strong democratic practices and dedicated tecnicos. Of all of the organizations included in the study, the organizations in Nayarit had the most member farmers using little if any agro-industrial inputs. Five members from every organization were interviewed and each had a deep knowledge of the ACCI/MICI approach and the science behind the techniques they were applying. Many had attended either local workshops or the ANEC organized workshops on ACCI/MICI. What was especially noteworthy was that, during the visit, there was no way of distinguishing the tecnicos from the farmers. During a visit of their collective demonstration plot-- where the three organizations were collaborating to test heirloom seeds against commercial hybrid seeds--farmers and tecnicos alike were sharing information and discussing the results they were observing. This was the dialogue of knowledge in practice!

Each of the three organizations had self-sustaining biofabricas and produced enough microorganisms and organic fertilizer to meet members’ needs. Two of the organizations were selling their fertilizer and microorganisms to farmers outside their organization and promoting ACCI/MICI among farmers that are not members of ANEC. The tone of farmer interviews was often giddy, members were excited to recount the traction ACCI/MICI is gaining in their community. Two farmers said that their neighbors were coming to them for advise instead of consulting the local government extension agents. “ ACCI/MICI is about to be big, really big… it was slow at first but things are gaining momentum… the only thing that would make the transition to ACCI/MICI happen faster is if we could offer our fertilizer and micro-organisms on credit. I bet you that in a few years, most of the farmers around here will be using ACCI/MICI.” (Don Gamboa)

Juayangarero, a local organization in Michoacán, is one of ANEC’s model ECCs. It is the organization that any visitor is taken to see and is likely the local organization that most closely approaches ANEC’s ideal in terms of democratic practices and the engagement in the ACCI/MICI approach.

Juayangarero has a thriving commercial enterprise; they commercialize hundreds of tons of grain every year and are able to support over 15 staff members, including accountants, 2 tecnicos, a manager of the biofabrica and worm composting operations. They have developed some of the newest ACCI/MICI innovations, including natural pesticides that they have tested with member farmers.

The head of Juayangarero, Ing. Olga Alcaraz, is an important figure in ANEC and a tremendous advocate for ACCI/MICI. She is both the head of Juayangarero as well as a member of the regional organization’s, REDCCAM, advisory board. Inge Olga has also been elected Secretary of ANEC’s National Assembly on multiple occasions.

As a result of Inge Olga’s leadership, Juanyagarero has developed a strong team of tecnicos, model-farmers, and model leadership that are promoting the ACCI/MICI approach among member farmers. Inge Olga has also helped promote ACCI/MICI among other regional organizations outside of Michoacan, drawing from Juayangarero’s experience, and the experience of Michoacán’s REDCCAM, to convince other farmer organizations of the benefits of the ACCI/MICI approach.REDCCAM frequently hosts workshops and meetings on ACCI/MICI and regularly hosts demonstrations for local organizations and organizations from other states. REDCCAM has also established their own soil-testing operations and a laboratory that will serve all of ANEC’s member organizations.

Juayangerero is an example of how effective an integral application of ANEC’s model can be for community-led rural development. The combination of good governance practices combined with strong democratic leadership and a team of effective tecnicos and model farmers has accelerated a transition to agroecology and laid the foundation for scaling ACCI-MICI up and out to farmers all over the state.

In an ideal world- where ACCI/MICI approach was fully implemented - local organizations would all be like Juayangarero. They would be strong, autonomous, self-sustaining and democratic. They would be able to produce their own inputs, have their own biofabrica that produced all the microorganisms, composts and seeds they would need. They would also have the equipment to do soil testing, a weather station that gave farmers up-to-date local information. Member farmers would be deeply knowledgeable about their land and their local agroecological systems and organizations would be able to pay for full-time tecnicos, that were also farmers in the local community, who could support members. This is an ideal, something to strive for but it is not, as of yet, a reality.